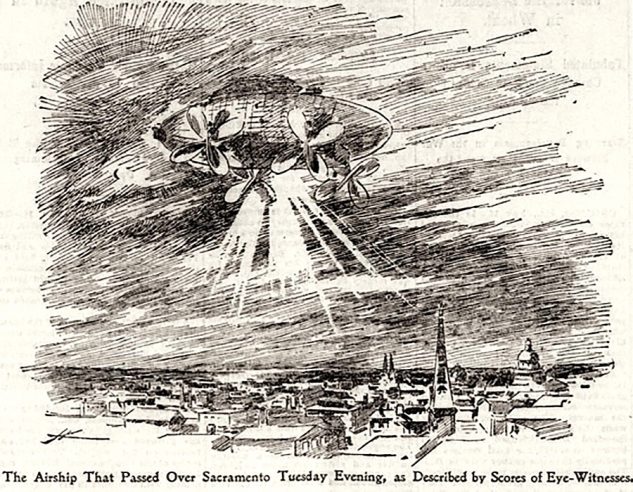

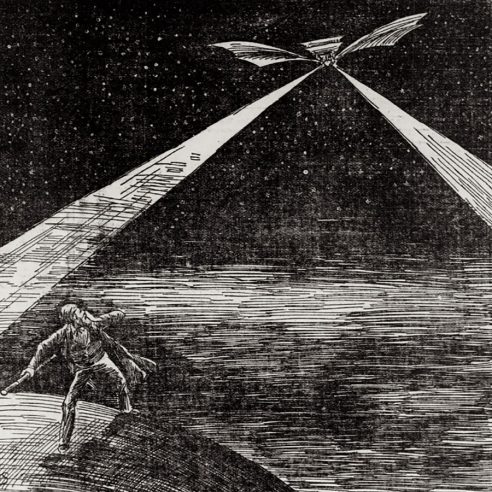

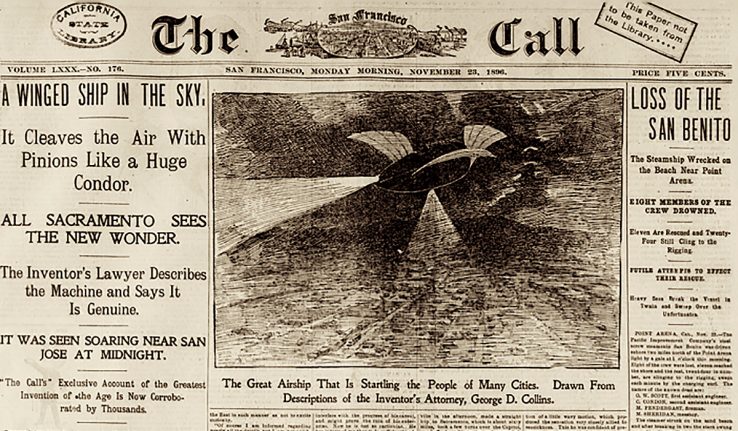

Half a decade before the first experiments of the Wright brothers, a wave of unlikely airship sightings spread across the American Midwest in an incident that has become known as the Great Airship Scare. It was America’s first big UFO craze.

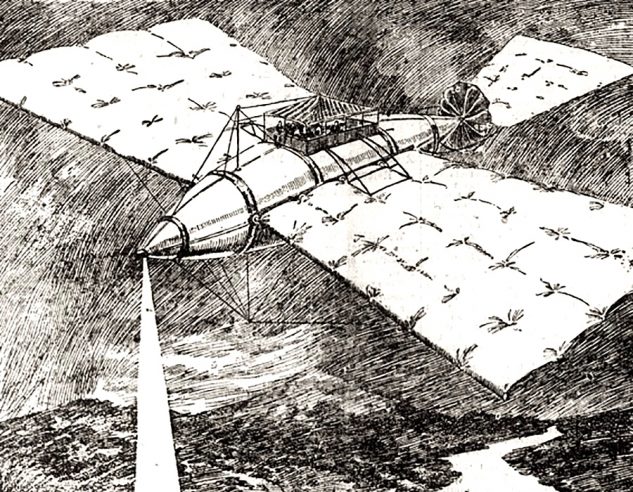

The quintessential encounter (and there were dozens of these) has a cigar-shaped and silvery airship landing in a farmer’s back field and one or numerous passengers being disgorged and interacting with the awed farmer and his kin. The airman appearing to be in charge introduces himself, describing the airship at his back as being of his own invention and asks for some water for his engines. There is nothing otherworldly or supernatural; it might have seemed perfectly plausible if it weren’t for the fact that no airships were supposed to be flying yet in 1896.

The question absolutely begs: Did it really happen?

It’s not impossible

A thousand reasons suggest that it didn’t, but first let’s list some reasons why it might have.

To begin with, there’s no earthly reason why airships couldn’t have been flying way back then. Lighter-than-air flight is nothing more than harnessing one of the simplest fundamentals of nature. Leonardo da Vinci had envisioned it centuries before and there’s reason to suspect that Mesoamericans built manned (or at least manable) balloons centuries earlier.

By the time of the Scare, several patents were already on file with the US Patent Office for all sorts of flying machines.

This said, why does the Great Airship Scare feel so much like the silliest of urban legends?

But it doesn’t make sense

Because it happened in 1890s America, that’s why. There is no sensible reason why any American would build a flight worthy airship, running steam engines and remain anonymous throughout the acme of his fame.

Airship sightings were front-page news in every paper from the Chicago Tribune to the Picayune Times-Courier and the American entrepreneur has not been born who wouldn’t milk a cash cow like that for every drop.

He could have been rich beyond the dreams of Avarice, but we are expected to believe that he landed his great ponderous airship in a few farmers’ fields with nary a misstep and then vanished into the mists of legend. It just can’t be.

So what really happened?

Consider this: it was imagined. It was a mirage. It was mass hysteria.

One of the very first bits of human literature ever written down was the Epic of Gilgamesh, from the third millennium BC. It follows Gilgamesh the king through a mythic journey to far-off lands and through the very underworld itself. There are, of course, gods and devils and torments at every turn, but there is logic and a pattern beneath it all. It strives to be as accurate a description possible of a very brutish world, using the only frames of reference the people telling it had available. So when demons belching fire erupt from the very ground, nearly burning Gilgamesh alive, we know that Sumerian traders have entered Anatolia and have seen volcanoes for the first time.

It is understandable human embellishment and we recognize it as such. Few scholar will argue that there were indeed giants in the Earth in those days. We realize all too well that a frightened human is an inventive one.

Likewise, skipping ahead a few thousand years, Farmer Brown had reason to be frightened. When the Industrial Revolution in America got into high gear, after post-Civil War Reconstruction, the first grim chapter in the saga of the American farmer was written. America was switching from being an agrarian to an urban nation then and farming was becoming a business instead of a livelihood. Expensive machinery was becoming the unwanted standard, farmers were experiencing their first bank debt and it seemed like bank scares were happening every other week.

Who can blame Farmer Brown for getting a little excited and telling a tale about something that never happened? Nobody got hurt, he might get his picture in the papers and it just might take his and his neighbors’ minds off their troubles for a spell. And so the telling spread.

If there were a continuum to be charted for this sphere of human experience, we might see classic mythology on one end, raw mass hysteria on the other. Throughout it we’d see the inventiveness of the human mind with peaks during times that were harshest. Explore that line of thinking just a bit further and one finds rational explanations for everything from Foo Fighters to Sasquatch.

Not all of our favorite historical mysteries will be solved in our lifetimes — and many of us prefer it that way. That doesn’t preclude the rational thinker, though, from following the self-evident analyses of these cases and decide that the simplest explanation is usually the correct one.

This story first appeared in Gatehouse Gazette 16 (January 2011), p. 7, with the headline “The Great Airship Scare”.