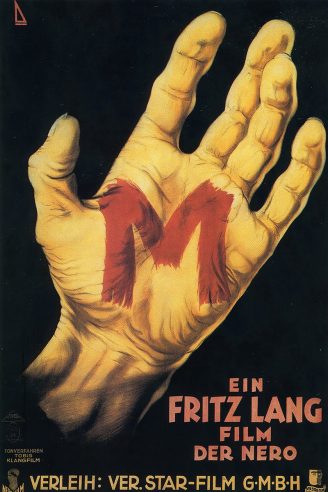

M (1931) is often named as one of the classics of cinema. It is high up there with the few other masterpieces and this reputation is well deserved, as I hope to make that clear in this review.

For the whole length of the film, director Fritz Lang plays masterfully with light, sound and shadow.

The first example is when we are introduced to the murderer. We do not see his face, nor quite his figure. We only see his shadow cast on an advertising column, falling right on a notice that warns the public about him and offers a reward, while he himself is talking to a little girl named Elsie: his next victim. Later, he buys her a balloon, all the while whistling “Hall of the Mountain King,” his trademark tune which he whistles compulsively and ultimately proves to be his undoing.

This scene to me is the key to the whole film. The murderer, played brilliantly by Peter Lorre, is seldom seen, but his presence haunts the city and the story alike like an ever-present shadow. Lorre makes him always seem small and haunted, so much that the viewer is left puzzled how so pitiable a person who is terrified by voices in his head can exert such menacing influence.

Next, we see the girl’s mother waiting for the return of her child. In the progress of this scene, Lang plays with sound and the lack of it. M was one of the first non-silent German movies, but it still employs a lot of silence for effect.

For example, after the mother of the little girl starts looking for her child we see various rooms, attics and staircases. Initially we also hear the calls of the mother, but then the sound stops. We only see silent, empty rooms, which greatens the sense of helplessness and loneliness. The following two scenes are again filmed in haunting silence: the little girl’s balloon, caught in telephone wires and her ball, rolling aimlessly from behind some bushes.

With very little effort, Lang manages to draw the picture of a city descending into paranoid chaos. There are people accusing one another, a pickpocket being mistaken for the murderer and the like. All these scenes are intertwined with the spirited but futile attempts of the police to find any clue. We also see the hands of the murderer writing a letter to the newspaper, again whistling his tune in stark and penetrating quality.

After yet another futile police action, this time on a underground joint, the gangsters of the city get themselves organized to find the killer. Coincidentally, the police have a meeting at the same time. We see the police force and the criminals making plans. First we watch the one party, then the other, then back again, their actions mirroring one another. The police and the criminals are depicted as equal organizations, operating by remarkably similar rules and united in their common hunt of the murderer.

These criminals are, in spite of their status, portrayed as a civilized, organized and rather likable lot. In one scene, just after the aforementioned police raid on a notorious gangster joint, the lady running it points out to the chief of police that none of “her boys” would ever even touch a child. Even the hardcore criminals would go all soft when watching children play.

Finally, the crooks come up with a plan which will become the murderer’s undoing. They enlist the beggars of the city to keep watch on every street, every backyard, never loosing site of single child.

When the murderer again lures a girl and buys her a balloon from the same blind beggar, again whistling his tune, he is recognized, marked with an M for murderer on his coat by another thug and soon driven into hiding in an office building, where the combined cream of the Berlin underworld follow to catch him. In the course of this, the police is alerted and comes rushing to the building too. The criminals, however, manage to get to the murderer first and drag him away. In their hurried withdrawal they forget the chief safebreaker, who in turn is duly arrested by the police.

This safebreaker is portrayed as a gentle soul, who breaks during interrogation. He tells the police about the intentions of his fellow lawbreakers: they seek to put the murderer on trial. The murderer there delivers an impressive, haunting and disturbing monologue in his defense, but is subsequently interrupted by the police.

The film ends in a real court of law, but we never find out its ruling. Before it is to be announcement, the scene cuts to the victim’s mothers with Elsie’s mother saying that either sentence will not bring back the dead children.

Fritz Lang makes a point of having both the underworld as well as the police, although on opposite ends of the law, doing exactly the same thing: hunting the murderer.

Interestingly, the underworld seems far better able to tackle this task, as they are well aware that their target is none of their own. They know much better whom or what to look for and, through the bums of the city, have the manpower to do so.

The police, instead, although highly motivated, simply intensify their efforts to hunt down a “normal” criminal. Only at the very end do they catch up with the murderer and only through a lucky arrest, caused by carelessness on the part of the criminals. This portrayal of police and underworld is a thinly veiled depiction of the social reality of the late Weimar Republic itself. The state is almost on the brink of collapse and only the efforts of both law enforcement and lawbreakers, to whom a breach of the status quo is bad for business, can keep society from slipping into anarchy.

This precise social picture, summed up in this film is another feature of what makes it so realistic. In the context of its own time, the film tells a story that very well could have happened like this.

The inherent reality of the plot, Peter Lorre’s masterful portrayal of the murderer and Fritz Lang’s play with sound, silence, light and shadow have seen to it, that even more than 75 years after its release, M has not lost its terror and its appeal. It is one of the jewels of early sound film, late German Expressionism and world cinema.

This story first appeared in Gatehouse Gazette 7 (July 2009), p. 21-22, with the headline “Shadow Show of Murder; M”.