George Chetwynd Griffith-Jones is one of the forgotten luminaries of the classic British Scientific Romance. A best-selling author and sometime rival of H.G. Wells’ at the beginning of the twentieth century, his work has been mostly forgotten by later generations. While much of them are steeped in the opinions and prejudices of his day, Griffith’s tales contain many elements that would lay the basis for the first great boom of science-fiction.

The Astronef series is a good case in point.

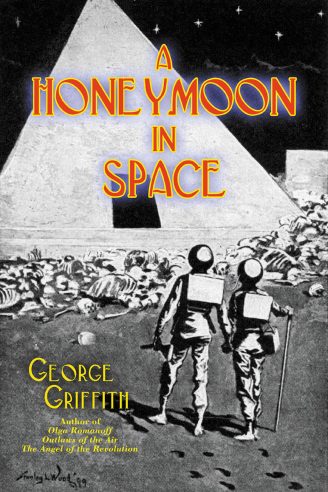

Originally serialized in Pearson’s Magazine over the course of 1899-1900, the stories were later novelized with some additional material in 1901’s A Honeymoon in Space. They follow the adventures of Rollo Lenox Smeaton Aubrey, Earl of Redgrave, and his new bride, the American Lillia Zaidie, as they travel through the Solar System in the Astronef, a vehicle propelled by the gravity-repelling “R. force” developed by Zaidie’s late father.

In each of the stories, the couple visits a new planet to explore and occasionally to battle its natives, unruly fauna and environmental hazards.

Overall, this type of narrative bears a close resemblance to the American “Edisonades” popular in this period, with heroic genius-inventor characters traveling to exotic locales in vehicles of their own creation.

Though similar in some aspects to the works of Jules Verne — himself a dabbler in the Edisonade from time to time — the Astronef stories are pure adventure, with less of an emphasis on the technical aspects of space travel (or on character development, for that matter) and more on the exploration of the Solar System. With their focus on alien monsters, ancient necropoli and aerial skirmishes, the Astronef stories lay a considerable amount of groundwork for later pulp science-fiction of the interwar era.

Similarly, Griffith’s notion of space shares many assumptions with later works. The Solar System discovered by the Astronef is organic, with different planets representing different stages of Earth’s “life cycle”.

Naturally, most of the stories focus on the worlds that represent the future of Earth, namely the Moon, Mars and the Jovian moon Ganymede, which are all inhabited by technologically utopian civilizations struggling to maintain themselves amid diminishing resources and ionizing atmospheres.

For the rest of the Solar System, life exists in either a vicious Hobbesian state of nature or, as in the case of Venus, an Edenic pleasure garden untouched by war or sin. (For a modern reworking of this concept, the reviewer would recommend the novels of S.M. Stirling’s alternate-historical Lords of Creation series.)

Overall, this conception is very much in keeping with the perception of Darwinian evolution prevalent at the time as a struggle toward perfection.

Unfortunately, this attitude tends to seep into the narrative. In Honeymoon, there are multiple assertions to the “higher” nature of the Anglo-Saxon race and many of the battle scenes do fall into the “kill without mercy for they do not deserve it” mindset. While this attitude never overwhelms the stories, it does give them an uncomfortable subtext that a modern audience must frown upon.

The voyages of the Astronef may not be great literature, yet they provide a fascinating look at a long-forgotten chapter in the history of science-fiction.

This story first appeared in Gatehouse Gazette 5 (March 2009), p. 16, with the headline “A Century Adrift; The Company of the Dead”.