Joseph Stalin was synonymous with the Soviet Union until he wasn’t. When Nikita Khrushchev, in 1956, formally denounced the vozhd, the man who had led his country through the nightmare of Barbarossa and emerged victorious, it came as a shock. The red banner flew from Vladivostok to Erfurt, from Murmansk to Tirana. World communism seemed inevitable. But Khrushchev knew Stalin had also hurt the Soviet Union in many ways.

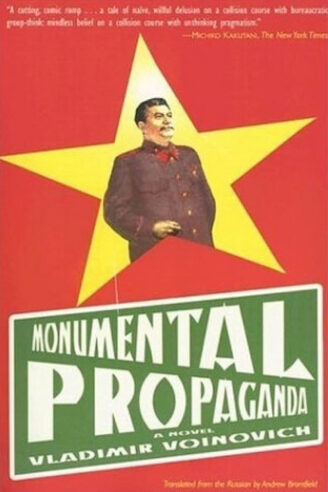

Vladimir Voinovich’s 2000 novel Monumental Propaganda, named after Lenin’s doctrine of monumental art, whose remnants dot the former Soviet Union, addresses that shock. In particular, it revolves around a statue of Stalin in a fictional Russian city that is brought into being by Aglaya Stepanovna Renkina, a local party apparatchik who is intensely devoted to the leader. (She survived Barbarossa) She is stunned when the statue is removed in the wake of de-Stalinization and spends the next several decades trying to cope with that loss. In her nostalgic delirium, she finagles her way into getting the statue established in her living room.

Monumental Propaganda is a book about great visions of history, and how they are all too fleeting. The Bolsheviks had made themselves the living embodiments of what they thought would be a better future, and had the world’s communist parties marching in lockstep. Stalin beat the Hitlerite hoards. This seemed immutable until the decision was made to denounce him by Khrushchev. It is the very sort of political about-face that inspired Newspeak in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four.

The book follows Aglaya starting in the early 1950s and tracks her anguish and her disorientation over the next several decades. Many prominent historical figures are name-dropped during this time, and a few show up in person, if briefly. Through this, there are a number of vignettes describing characters who show up for only a scene or two. One memorable example concerns the sculptor who created the statue. They allow Voinovich to look at the fate of the Soviet Union with a Michener-esque scale, an impressive feat given that the book is just shy of 400 pages.

Through the novel, there’s a faint sense of absurdity that only intensifies as it goes on. Voinovich made his name as a dissident writer in the late Soviet Union, and continued his dissent under Yeltsin and Putin (he died in 2018). This is palpable through the novel. Voinovich is furious at a government whose ideology promised the world and whose apparatchiks could only deliver stagnation and decay. Time and again, human foibles override lofty idealism. Monumental Propaganda is a searing look into the dysfunction of the Soviet Union, and an insightful meditation on how the best-laid plans of mice and men gang aft agley (with apologies to Robert Burns). Voinovich is a latter-day Russian Ecclesiastes, calling it all vanity.