Veterans were a strong public presence in the Weimar Republic. A total of 1.4 million disabled veterans came back from the war, and the republic provided them with occupational training, free medical care and pensions. For the severely disabled, particular jobs were granted special protection.

Still, the republic was ill-rewarded for the care it offered, above all because expectations kept rising as the economic situation kept worsening and there was only a certain amount of money that could be devoted to this cause. Veterans normally didn’t support the republic.

By 1919, veterans were represented by seven different organizations, of which the Reichsbund der Kriegsbeschädigten und ehemaligen Kriegsteilnehmer (National Association of Disabled Soldiers and Veterans) was the most numerous with its 600,000 members and ties with the Social Democrats.

But the most relevant was the Stahlhelm (Steel Helmet). Founded in Madgeburg as a small, regional organization in 1918, by the following year it had already grown to national recognition. With 250,000 members in 1925 and a markedly rightist policy, the Stahlhelm didn’t really have a political program, but its “street politics” became strategic for the affirmation of nationalism. Its strong believe in the legend of the “stab in the back”, its celebration of the valor of the frontline fighters and the alleged “community of the trenches” became very popular in a society that was heavily militarized in so many aspects of life and propagated the model for a renovation of that society. In time, the Stahlhelm got very close to the NSDAP.

But not all veteran organizations were nationalistic. The Stahlhelm‘s main opponents, the Reichsbanner, proposed a completely different interpretation of the war and its soldiers, one that emphasized the brutality of war, the hardship soldiers were put thought and the tension-ridden relationship between officers and enlisted man.

Besides, many veterans still suffered for the repercussions of war in their lives. World War I had created injuries of unprecedented cruelty, not just in the body but also in mind. Ironically, this allowed shocking advance in all camps of medicine.

Shell shock

War techniques had evolved a great deal in the decades previous to World War I. The cannon barrage of the Napoleonic Wars and the automatic weapons of the American Civil War were considered mindblowingly powerful, but nothing prepared neither officers, nor soldiers, nor civil people to the carnage of World War I. The firepower of World War I artillery was simply something never seen before.

It was in this environment that a new form of injury was first recognized and given a name: the war neurosis. A state where the soldier was not physically injured, but he was clearly damaged and had violent psychological reactions.

The term shell shock was coined by a medical officer, Dr Charles Myers, in 1915. Initially, it was believed to be physical damage to the nerves suffered by soldiers exposed to heavy shelling on the front and those who were buried by such shelling — sometimes as long as 18 hours. But soon it was clear that even soldiers who were never near to the frontline suffered from the same illness and so doctors realized these men simply could not cope with the horrendous circumstances of the new industrial war.

The reaction to this “new” war illness was initially very hard. These soldiers were sometimes considered cowards because they could not cope with the demands of war. Cases were particularly severe among officers, who had to “manage” the lives, and deaths, of the soldiers under their command. But as cases piled up of men who could not eat after stabbing an enemy in the gut, who could not see after being a sniper on the battlefield, those who suffered from nightmares or nervous ticks, it became clear that the war trauma — though it left the soldier physically untouched — gravely affected his mind and emotions.

During the first years of the war, this was met with skepticism, especially by the army leaders. Soldiers were often suspected of pretending to be ill and anyway, the main object of any cure was to get them well enough to be sent back to the frontline. The ones who broke down were considered cowards and were a shame to themselves and to their family since a man — especially a military man — should have been able to cope with any crisis.

But as the years stretched, doctors started to understand that emotional injury could be as severe as a physical one and could affect the body just as cruelly. Then they started studying the mind’s reaction more closely. Psychology and psychoanalysis were employed ever more often and leaped ahead in treatment and understanding.

The war, such terrible experience, was instrumental in a definite advancement in these fields of medicine.

The broken faces

World War I is possibly the war that most disfigured the soldiers who fought it. The “advancement” in artillery and weaponry, which could cause unprecedented damage to the human body, went alongside dramatic advancement in medicine, which could save men who would have previously been doomed. But the physical scars would remain. World War I is particularly remembered for the horrid facial injuries of so many veterans. Beside, trench warfare seemed to be diabolically conducive of facial injuries as soldiers would bring their head over the trench to watch out.

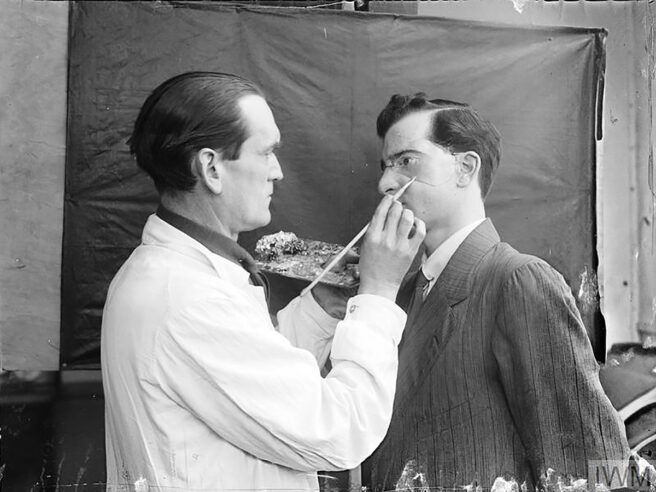

Plastic surgery was another field of medicine that advanced dramatically during the war. To some battles, the field hospitals received thousands of injured soldiers, and doctors learned very quickly what worked and what didn’t. But as for the disfigured, the main goal was always to save their life. Aesthetics never even come into the equation. If this may have been well and good on the battlefield, it proved to be terrible once the war was over.

Shrapnel facial wounds were terrible to behold. It took away whole parts of the face — noses, ears, jaws, sometimes half of a face. These soldiers could and were saved in the field hospitals, but once they went home, their life was forfeit. They became monsters in their own eyes, and many just retreated from social life. Special retirement houses were set up so that they could live among themselves and never have to see an undamaged human being again.

But the numbers of such wounded were so staggering that different solutions had to be found.

Sir Harnold Gillies was a pioneer of this field. In his hospital, dramatic advancement in plastic surgery was made, but the extent and severity of the facial injuries might be so great that alternative solutions must be employed. Dr Gillies was one of the firsts to work together with artists, especially sculptors, to create metallic masks that would recreate a men’s whole face, so to enable him to continue his life. This was a long, expensive process, and only a few of the thousands facial injured soldiers could afford it, but it was a path followed both in France and Great Britain. It only lasted a few years. At the beginning of the 1920s, all facilities of this kind had been dismantled.

It was ascertained that a mask — which was a think layer of usually copper and carefully painted to match the man’s skin color — could only last a few years before starting to look very battered, still veterans kept wearing them beyond that state.

Very few of these masks still exist today. Most of them were probably buried with their owners.

This story was originally published at The Old Shelter as part of an A-to-Z challenge about the history of Weimar Germany, April 25, 2018.