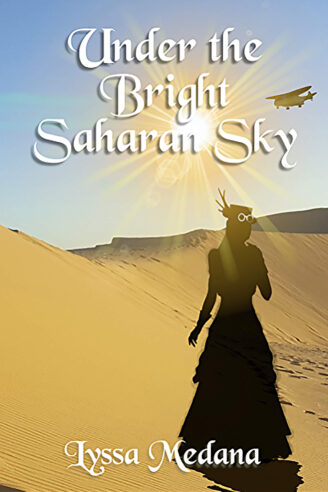

Under the Bright Saharan Sky is Lyssa Medana’s sequel to her fantastic debut novel, Out of the London Mist. We return to the characters of that novel as they go on a new adventure. I finished my review of Out of the London Mist with a wish that these characters would make the Saharan expedition mentioned in the book. To my great pleasure, they do just that in Under the Bright Saharan Sky.

Think of this book as a cross between Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, with a dash of steampunk fantasy. A third or so of the book is traveling through Europe en route to the Sahara (with a good bit set in Cairo), and you get a feel of all these different cities. It resembles something of a fantastic Baedeker.

Once the journey begins, you begin to see why Medana titled her novel the way she did. Much like how Out of the London Mist almost suffocated you with fog, this book can feel like you are tied to a stick being roasted slowly by the sun. The desert is lonely and desolate, with only ancient Nubians and marauding Bedouins to provide you company. Medana deserves credit for originality by having her plot revolve around the Nubians rather than the more clichéd Egyptians. The plot reaches its high point when they discover what is actually in these Nubian tombs, leading to a satisfying conclusion.

In some ways, though, the plot of the book is secondary. Its major strength is its characters. Leading them all is the eccentric John Farnley, who has the ability to see paths through the aether, the magical field that provides this world with its magical technology, and can from there navigate the world with ease. Medana averts the common trope about making stories about people with powers about their powers, and gives Farnley the depth and the swagger of the likes of Phileas Fogg. Farnley is a conflicted man and a complex character, who has to reckon with what the Victorians expected of a gentleman versus what he himself wants. In this regard, he is the ideal protagonist for this sort of thing.

Farnley is not the only interesting character. He meets many people along his journey, and brings several along with him. My favorite is Hammerhand, the golem from Out of the London Mist, who gets to shine in this book. He is a machine among men and trying out to figure out his place in a world of flesh and blood. Conversations between him and various other characters provide the best dialogue of the book, and this is involving a character who cannot actually speak! It’s quite the accomplishment.

My only complaint is about Medana’s portrayal of the Africa in which so much of the action is set: for most of the book, the only Arabs (as this is in Egypt and Sudan) are portrayed as thieves, fellahin or marauders. (There is something at the end that addresses my concerns to a degree, to Medana’s credit.) Given how vividly she portrayed the Jewish area of London in Out of the London Mist, I was disappointed that her depiction of these countries did not have any sympathetic locals heavily involved in the story. Not unlike C.J. Sansom in Winter in Madrid (my review here), Medana never allows Egypt and Sudan to be anything other than foreign.

But that is only one aspect of the book. Everything else is spectacular, the sort of steampunk adventure that keeps readers coming back to the genre.