Over the whole nineteenth century, the Western world in its entirety had been moving in the same direction: away from the countryside into the cities. Away from a rural lifestyle into industrialization and generally into a more inclusive, if maybe more lonely, society. Germany had been inside that general flow.

The great shift, which had started in the nineteenth century with the Industrial Revolution, quickened its pace after the war. Although German society, like all other European societies, remained mostly rural, the move from the countryside to the cities accelerated. And it wasn’t just a move from one place to another, it didn’t just change people’s lifestyle, but also their minds. The way people understood life and the ideas they were willing to accept change dramatically as they moved from one environment to the other.

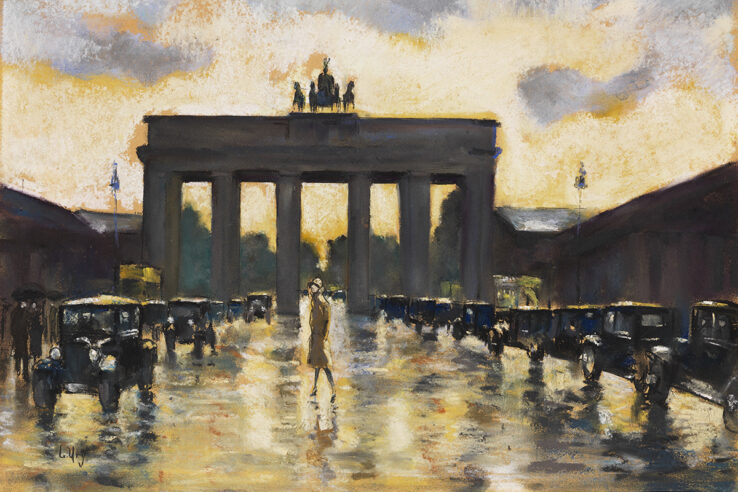

The divide between village and city was possibly at its highest at this time. Life still flew as it had for the past hundred years in the villages, but in the cities huge social changes were happening.

The shifting role of women was one of the most shocking. Women had had to fend for themselves during the wartime. They had worked like men, looked after their own family without the help of a man. The republic was giving them new rights, new freedom and to some extent new power. Women started to think about themselves in a different way and to have different expectations on life.

The new contraception methods, which were becoming more common and more commonly accepted, enabled them greater control over their maternal life, which caused a huge change inside the family, its structure and its life. Couples could decide when they wanted children and how many they wanted. Family — at least in the cities — became smaller. Many women chose to have children later in life or to have none at all, which, in a time of demographical depression, was considered unpatriotic. But more shockingly still, now women could decide to do with their sexual life whatever they wanted, just like men had been doing.

Cities also offer a lot more opportunities than the villages ever had. The old path that led the young on the same working and aspirational life of their fathers was breaking. Educational opportunities in the city meant a young person might become whoever they wanted. And often they did want new opportunities. As their expectation of the future shifted, young people sought new jobs and a new way of life, creating one more fracture with the older generation. There was a strong sense that youths were revolting against their elders about everything: ways of life, aspirations, expectations, values, social behavior.

Besides, this world was slowly filtering into the countryside as well. Not all who worked in the cities left permanently. Many went back to their villages at the end of the day or the working week, bringing with them ideas, attitudes and aspirations from the cities. Women working in domestic positions were instrumental in this shift, since they were numerous and their role in the education of the family was very relevant.

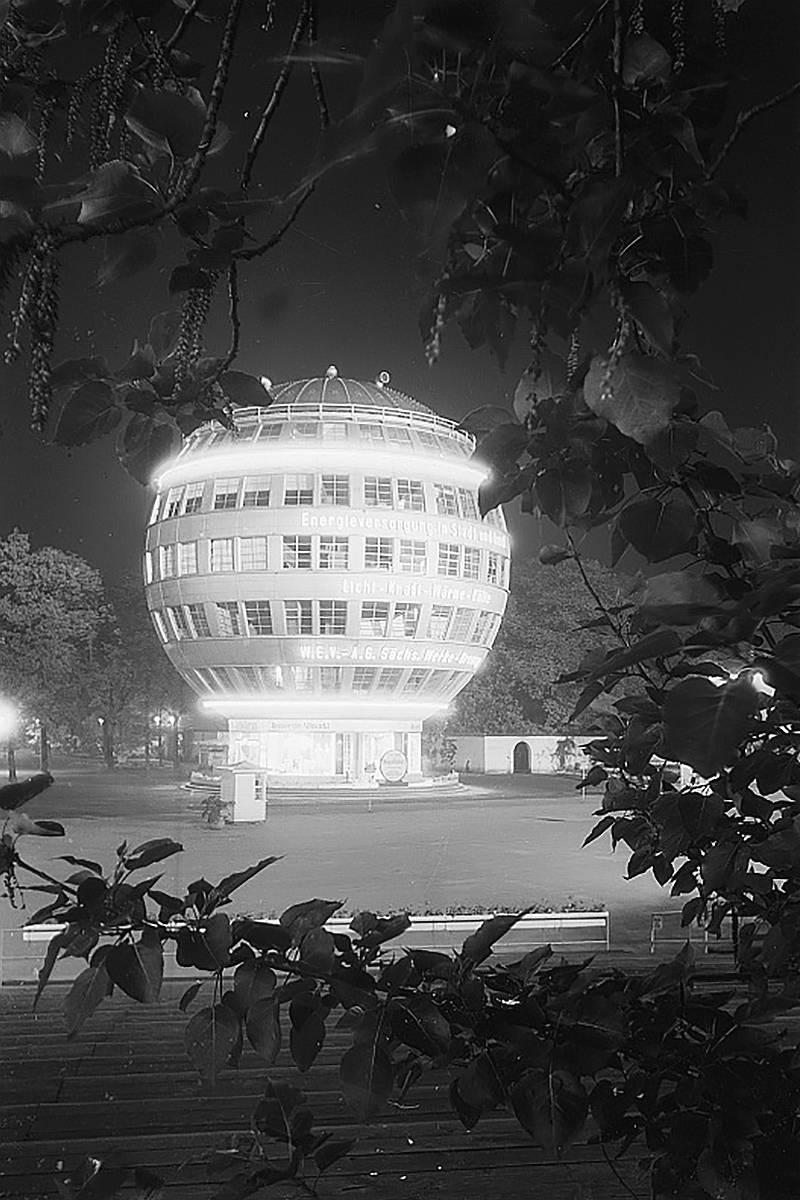

Radio, theater and itinerant cinemas were becoming commonplace, propagating the new ways of life even in faraway places.

But it would be wrong to think this was happening in a general consensus. Despite everything, the old “Wilhelmine” ideals of property and rigidity were still prevalent and accepted in Germany. Women were more affected. The perceived decadence of the entertainment and the arts was also very strong. There was a general feeling that the world was becoming corrupt. Especially in the cities, this dichotomy between the very new and the very old became extremely sharp.

This story was originally published at The Old Shelter as part of an A-to-Z challenge about the history of Weimar Germany, April 18, 2018.