When we think about the Weimar Republic, most likely we think about the time of right-wing power. Certainly, many authoritarian forces were at work in the republic, but this was also the time of a left government, one that shaped the social life of Germany profoundly.

The Weimar Republic was a relatively short experience in the history of Germany. It may even be true that the republic was too weak and unloved to ever be successful. But it was still the first democratic regime of Germany, the first time left ideas got out of the rooms of philosophers to get into the thick of everyday life.

The SPD was a socialist party with a long history dating back to the 1800s, and when the twentieth century opened it was the biggest party in Germany. Yet it had never been at the guide of the nation until Prince Max von Baden consigned that power in their hands.

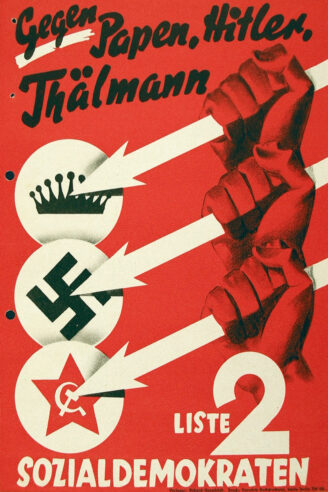

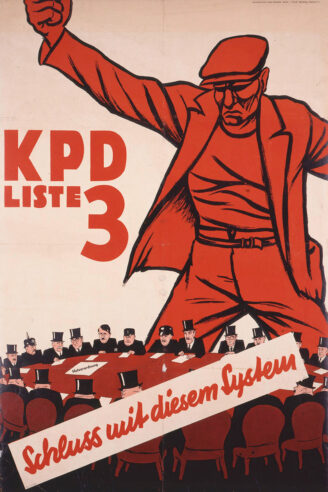

Unfortunately, the SPD was never able to create a parliamentary majority that would actually administrate the country. Fragmentation was the keyword of the Weimar Republic. Just like the right, the left counted a myriad of little political entities and movements, as well as two big parties — the SPD (Social Democrats) the KPD (Communists) — who never found any kind of agreements.

This is one of the strongest arguments against the left: they were never able to create the cohesive coalition that would have made the difference. Adding the many political crises that arose from the lack of a strong parliamentary majority, it becomes easy to see why the population never thought that the left was able to administrate.

The gap between the SPD and the KPD didn’t help. Together, they were the major forces against the right, but there was always great diffidence between the two parties. In particular, the KPD never forgot that in 1919 the SPD had preferred to side with the army to suppress the revolution, which ended in the death of many communists, including the leaders Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg. The KPD always considered the SPD as good as traitors after that.

On its part, the SPD was always diffident of the bond between the KPD and Bolshevik Russia. There was indeed very small room for agreement.

German Jews and the left

The majority of German Jews gravitated toward the left, finding there their natural political place since the right was mostly antisemitic — even when antisemitism was not the main point in the party’s agenda — and the Zentrum was strongly Catholic.

Besides the left suited them quite fine, since the left acted on more liberal ideas than any previous administrator in Germany and supported freedom of expression and full citizenship rights for all Germans. The left was also the side of the avant-garde, which was an art movement but also a way of thinking about the future.

Many of the Jews involved in politics were intellectuals. They worked in the field of communication, both for the SPD and the KPD. They were also involved in many of the revolutionary provisions of the republic. Their overrepresentation in the life of the republic was one element which instilled in the larger German population the idea that Jews were controlling their political as well as cultural life. Many believed that Jews were making a Judenrepublik (Jewish Republic) out of the Weimar Republic, which added to their little love for the republic and willingness to listen to antisemitic propaganda.

Left-wing intellectuals

As in many other countries, intellectuals were prominent inside the left, at least in numbers if not in power. Left intellectuals incarnated most of the republic ideals. They were mostly pacifists. They thought the law should be equal for everyone and more rights should be given to more people. It was them who pushed for larger participation of women and Jews in the republic’s life; them who wanted abortion and homosexuality to be erased as prosecutable crimes.

One would expect them to be among the strongest supporters of the republic. This was not the case. There was a divide between the left and its intellectuals, who mostly belonged to the middle class and, in small numbers, to the aristocracy. They had little to do with the majority of the members of any left party, who mostly belonged to the working class. The leaders of these parties, including the SPD, thought the majority of their members were not interested in abstract ideals of freedom but rather in more pressing problems of everyday life, like employment and the inflation. This created a divide between the left and its intellectuals, who — far from being champions of the republic — usually gave just lukewarm support, disappointed as they were in a republic that wasn’t doing a good enough job, leaving out of its action many important questions regarding freedom.

In truth, the Weimar left had many qualities and many liberal aspirations, but it never found the necessary unity to make those ideals become a reality.

This story was originally published at The Old Shelter as part of an A-to-Z challenge about the history of Weimar Germany, April 13, 2018.