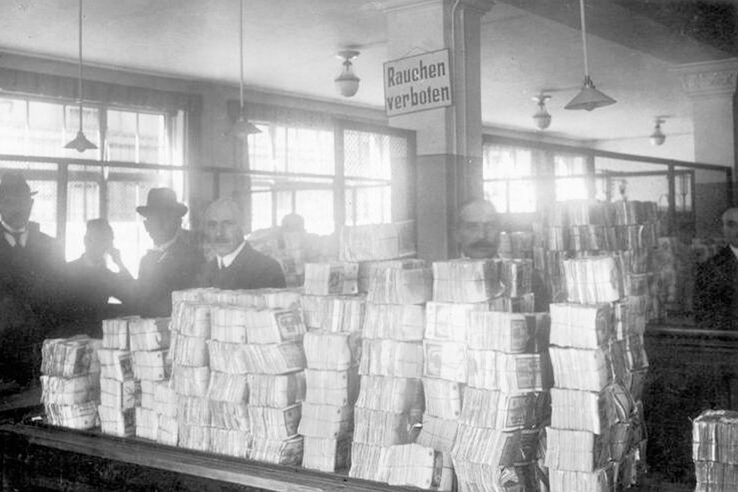

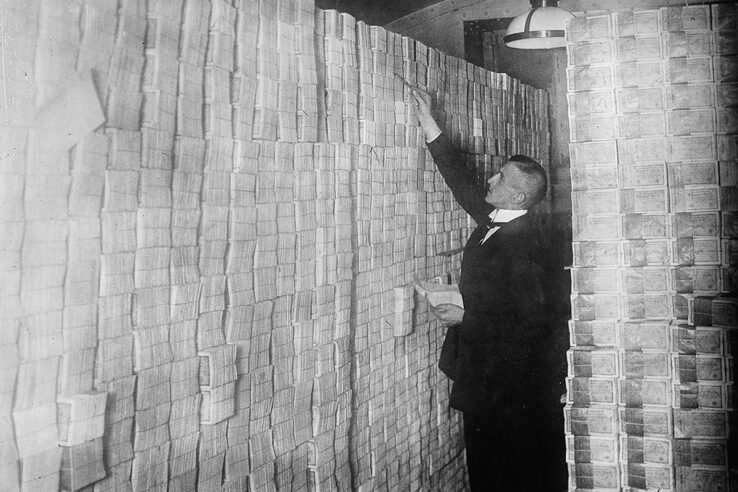

When we hear about the Weimar Republic, most of us think to wheelbarrows of banknotes used to buy one loaf of bread or stakes of notes used to fuel stoves. In short, we think to the hyperinflation of the middle 1920s.

We might think hyperinflation was a specific German situation since we seldom heard of any other such. It wasn’t. In fact, most countries after World War I knew a period of hyperinflation, an occurrence that had never been uncommon after a war. But the German case was peculiar, researched and dissected in detail ever since because a lot of data were available in a time when data and charts were becoming more common. And anyway Germany was from the beginning a different case from all the others.

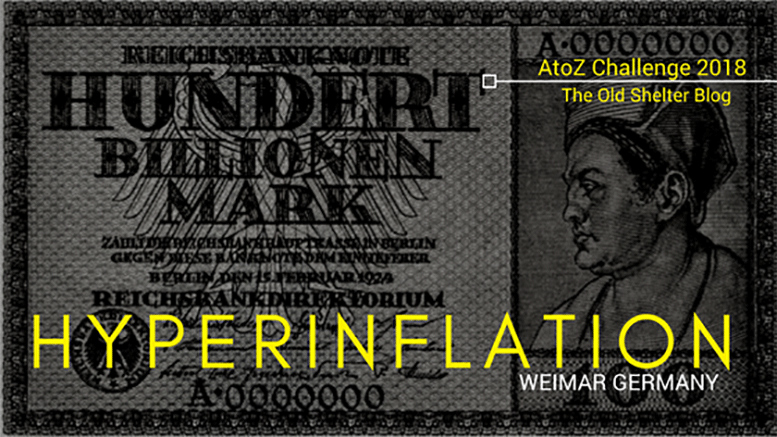

It isn’t easy to explain the hyperinflation, which took into account many different causes, both economic, political and social. What is certain is that it had devastating consequences on the population. Money lost value by the minute. Tales like the one of the man who ordered two coffees at the bar and paid two different prices because between the first order and the second the price had risen might be more legend than reality, but it was close enough. In 1918, one loaf of bread cost a quarter of a Reichsmark. In October 1923, at the height of the hyperinflation, it cost 80 billion Reichsmark. The largest banknote at that time had a face value of 100,000,000,000,000 (100 trillion) Reichsmark. The official change was 4.2 million Reichsmark against 1 dollar.

Inflation actually started in Germany before the war. Germany abandoned the gold standard and resorted to borrowing rather than taxation to sustain the increasing war costs. Everyone expected to be short. Germany thought they would be able to repay all debts with the loot of the war and anyway, debts were not going to rise too high.

But the war lasted for years, and in the end Germany lost it.

Germans met with horror the financial punishment of Versailles and just about met the first installment in 1922. By then, it was clear to the Weimar government that meeting any subsequent installment was impossible. But this was only four years after the war and the attitude was still very harsh on Germany. Her requests for a more lenient reparation plan fell in the void.

In that same year, the government order to increase the print of banknotes in the hope to stimulate the economy, a plan that industrials met favorably since this made the Mark cheaper, which meant easier exports. It also meant they had lower costs for their workers. It was risky, German economists understood that, but they thought this was going to be a short-term resource, just intended to help the economy to rise.

But the Allies didn’t take this too happily. Most of them thought that this was a ruse and Germany was intentionally ruining her economy so that it would become apparent that meeting the reparation costs was impossible. In early 1923, France and Belgium — ignoring the rules of the League of Nations — invaded the Ruhr, German industrial district, hoping to get reparations paid with goods.

The German government invited the Ruhr population to a “passive resistance,” which essentially meant a general strike. Every activity ceased in the Ruhr, the chief producer of wealth in Germany. Which meant France and Belgium didn’t get their money, but so did Germany.

Even if workers were not producing anything, they still had to be paid, since their strike was supported by the government. The only way to pay such a number of people was to print more money.

That’s when things got out of control. That’s when the banknote-burning stoves happened.

In September 1923 Germany had a new chancellor, Gustav Stresemann, who had different ideas about how to cope with the reparation costs. Rather than playing the “impossibility” card, he thought a parlay with the Allies was the best bet. He immediately started meetings and talks, and in November a plan was in place, the Dawes Plan, devised by an American banker. The US accepted to back a new German currency with gold, the Rentenmark, and set more realistic targets for German reparation installments.

When the Rentenmark replaces the Reichsmark, and twelve zeroes were cut from the prices, prices in the new currency became stable and the inflation normalized.

The worse of the hyperinflation had passed, but not its consequences. It is widely believed that the hyperinflation contributed to the rise of the Nazis. It certainly raised doubts about how competent a liberal institution would be in weathering an economic crisis. Germany was going to discover this when the 1929 crash came.

This story was originally published at The Old Shelter as part of an A-to-Z challenge about the history of Weimar Germany, April 9, 2018.