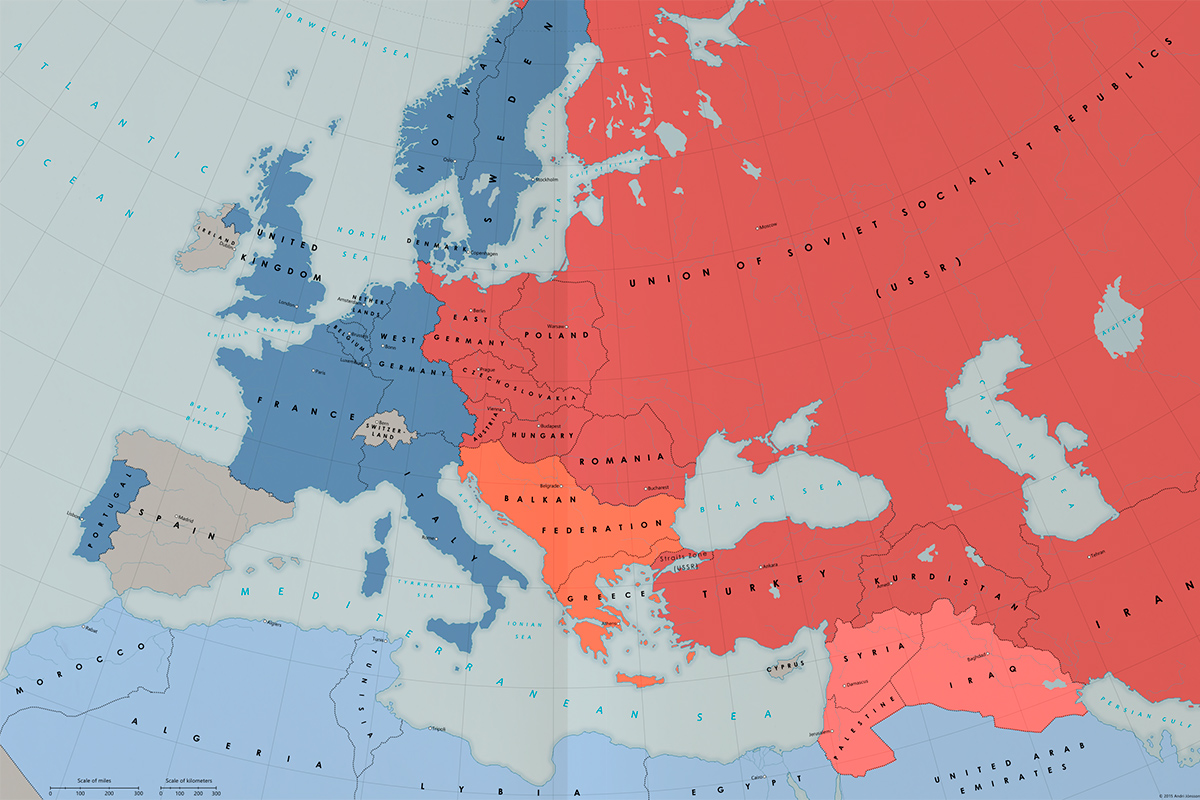

Northern Ireland can feel far away from the rest of the United Kingdom. Its political party system is different from Great Britain’s. Its politics are intensely sectarian in a way that seems out of place in modern Europe. The level of violence it sustained in the twentieth century makes it an outlier in post-1945 Western Europe.

We tend to think of the United Kingdom as a peaceful Western democracy committed to the values of justice and peace. Those of us who have studied its history know that the truth is more muddled. That postwar period saw the birth of the National Health Service and other aspects of the welfare state, but it was also the time Britain left Palestine in civil war, employed a brutal system of concentration camps in Kenya and did much the same in Malaya.

But none of that violence was as old as the one that plagued Ireland.

The conflict came to an awful, brutal head in 1972, in a city so contested that Catholics and Protestants couldn’t even agree on its name — and still can’t. The mostly Catholic nationalists call it Derry. The mostly Protestant unionists call it Londonderry.

Events were sparked by a march in Derry’s Bogside neighborhood by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), a nonviolent civil rights group that demonstrated for the rights of Catholics. Their methods were consciously modeled on the African American civil rights movement in the United States. They marched in protest against Operation Demetrius, the British Army’s systematized internment of those suspected of being involved with the Irish Republican Army (IRA), which had been waging a war of bombings and assassinations against Britain. It was in the Bogside that the British state showed the iron fist concealed behind its velvet glove.

Paul Greengrass dramatizes the butchery that ensued in Bloody Sunday. It is, like other films about historical atrocities, a sparse one that lacks melodrama. From the beginning, you feel the cold, cruel inevitably of its miserable ending. The specter of British lead haunts every scene until it comes blasting out of their gun barrels, shedding any democratic veneer.

One of this film’s strengths is its scope. It alternates between the NICRA organizers, the protesters and soldiers on the streets, and the British Army command trying to control (as their commanders would put it) the situation. It feels a bit like a war epic at times, in the way that some movies about civil disturbances can feel like war movies, and it works to great effect. In a real sense, Northern Ireland was a war zone, where the state deployed violence against partisans deploying violence. In some cases, the state allowed partisans to deploy violence on other partisans. All of these groups deployed violence on the innocent and peaceful when it suited them; this film is about one of those incidents.

A standout performance is given by James Nesbitt, who plays NICRA organizer Ivan Cooper. Nesbitt provides Cooper with the immense pathos of a man who desperately wants to believe in the goodness of his fellow human beings, but who sees that his faith has been tragically misplaced.

The film allows Cooper more humanity than other characters. He bickers with his wife over the time he spends with NICRA, but the foundation of their relationship is solid as bedrock, with some touching moments. Nesbitt reminds us that great figures of history were human beings, not deities, and that they had their foibles and flaws much as we do.

Bloody Sunday is also a meditation on the industrial state. Modern government can be incomprehensible to its citizens with its machinations behind closed doors. Decisions can appear conjured out of nowhere to those not inside the halls of power. But at their core, governments are instruments of death. In political science, government is defined as “a monopoly on the legitimate use of force.” At the Bogside, the British Army may not have inspired obedience among the Northern Irish Catholics, but, as this film excruciatingly shows, they had the monopoly of violence.