It is often argued that it’s easier to say what Expressionism was not, rather than to say what it was. Diverse and eclectic, this movement stressed deconstruction rather than building, individuality rather than the communion of feelings and experiences, making it inherently difficult to define.

Some say that rather than being a way to create art, a distinguished style or method of creations, Expressionism was more of a state of mind. The way artists felt about themselves, their society and the future of that society was more important than the way they expressed that feeling.

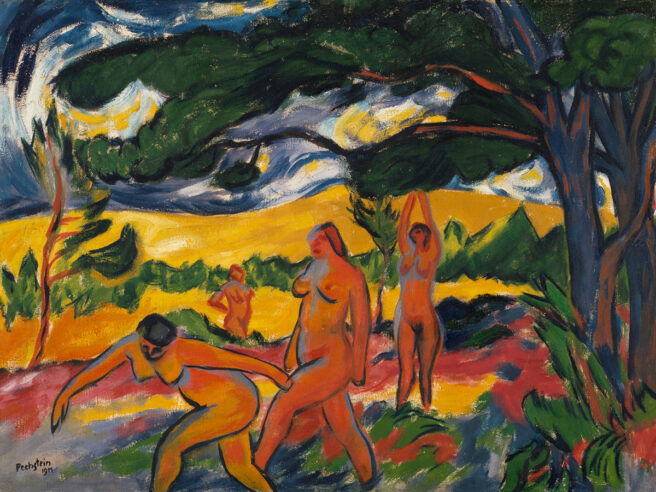

Although Expressionists maintain — with a certain amount of truth — that Expressionism had always been present in German arts, no matter how far back one looks. Though 1905 is the generally accepted date of birth of the movement, that is the year when four architecture students established the group of Die Brücke (The Bridge) in Dresden. Their intention was to create something new by looking back at a more authentic life and ways of feeling, one which modern humanity had lost.

The term itself is thought to have been coined by Czech art historian Antonin Matejcek in 1910, primarily to oppose this form of art to Impressionism. Expressionist artists never called themselves such.

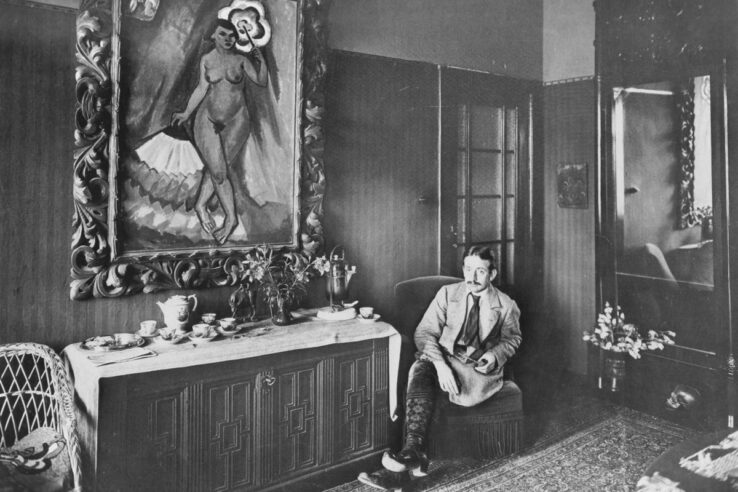

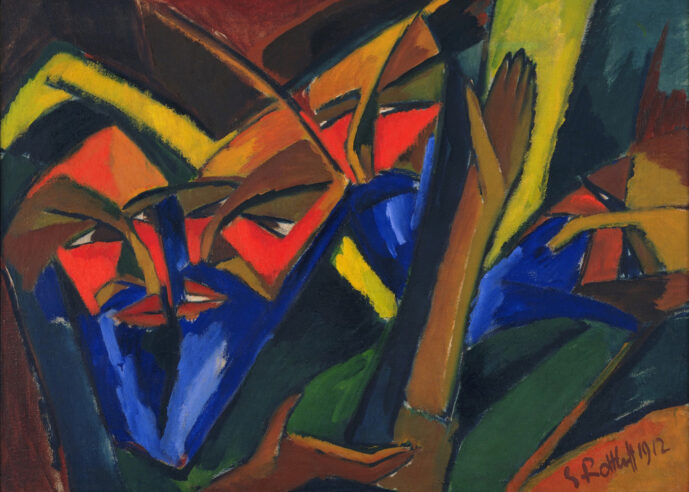

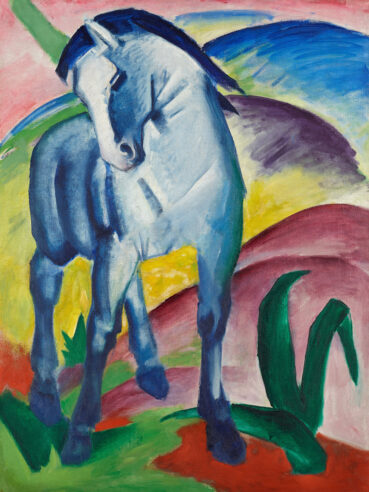

In truth, Expressionism had started to manifest even before the beginning of the twentieth century, in the last stages of Impressionism, to which it consciously opposed itself. While Impressionists tried to express the world around them in new, less stylized ways, Expressionists sought to express what was inside the human being by projecting it outside. Art came from within them, from their personal experience made universal. They tried to give a visual form to their times of anxiety when German society — like all European societies — was moving from an agricultural lifestyle to new, urban ways of life, with all the sense of alienation and powerlessness that came with it.

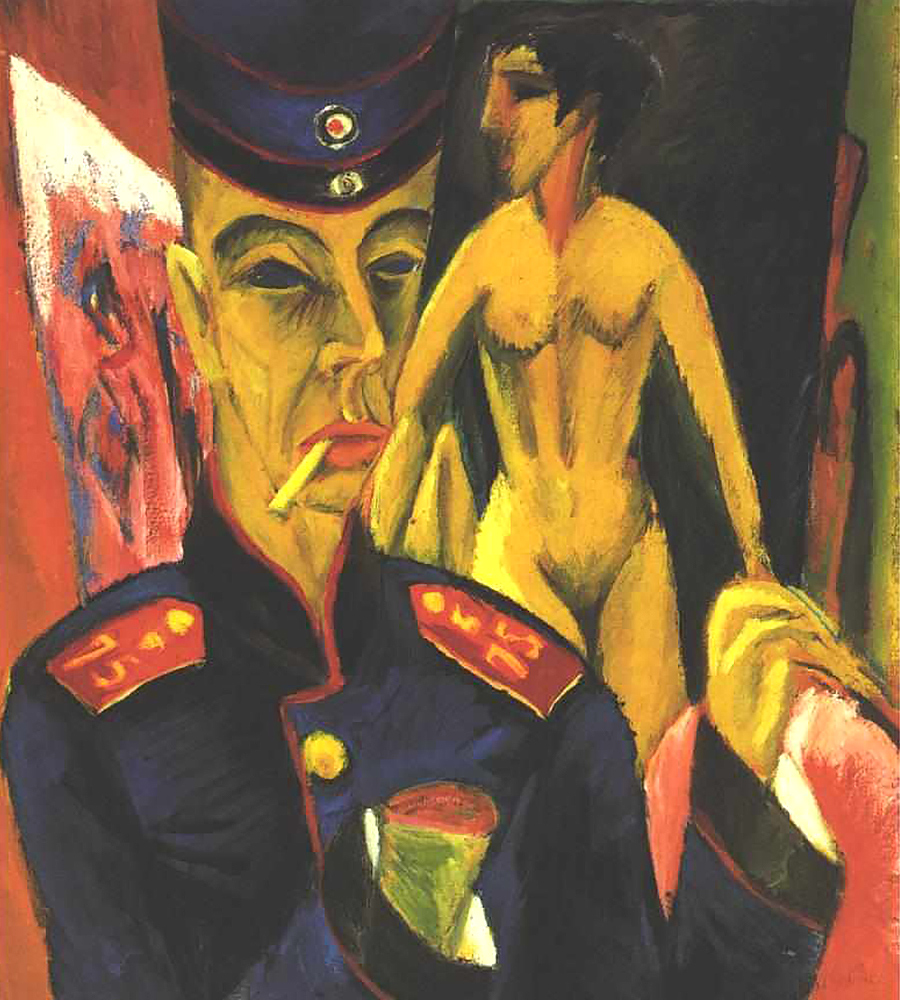

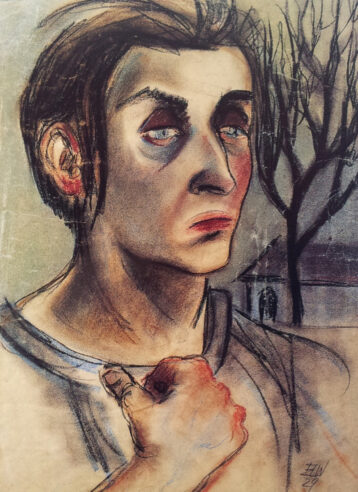

Many Expressionist artists took part in World War I. Many lost their lives during the war. The ones who survived turned their attention to the horrors of war, expressing their feelings, their anxiety, their damaged souls with art that consciously tried to elicit an emotional reaction by creating shock.

German Expressionism was primarily a visual arts movement. Its language was one of jarred lines, crooked shapes, violent, unnatural colors. Especially after World War I, it concentrated on the more grotesque physical human characteristics in an expression of the horrors of war that is hard to ignore.

The highest form of Expressionism was probably on stage, in the theaters, but especially in cinema. This medium that was in itself new and unexplored gave the opportunity to create a new language made of the stark contrast between light and shadow and the crocked, alienated, crazy shapes that were common in other Expressionist visual arts.

Literature also adhered to Expressionism. It gave voice to the inner feelings of the soul in a hallucinated, often broken narrative that produced stream-of-consciousness pieces rather than true narration.

When Expressionism died is still up for debate. Some critiques say it started to lose steam in the mid-1920s, because its abstractedness both of language and concept was difficult to understand to a majority of the public. It is sure, however, that the rise of the Third Reich, which dabbed all modernistic art as degenerated, whipped it away. And so Expressionism, which was the defining visual form of the Weimar Republic, died together with it.

This story was originally published at The Old Shelter as part of an A-to-Z challenge about the history of Weimar Germany, April 5, 2018.