In 1521, Vasco Núñez de Balboa made the first Spanish sighting from the east of what would come to be known as the Pacific Ocean. The journey had been arduous through jungles and across mountains, and interrupted by attacks on locals to gather gold and pearls, but it came to an end with a celebrated connecting point to fill in another empty space on their globes.

Twenty years before, on Columbus’ third voyage, it had first become clear that there was a good deal of land unknown to Europeans still separating them from the coveted trade of the “South Sea” near India and China. Ferdinand Magellan would show that there was a long way around it by sailing south and that the world could be circumnavigated (at least, the few survivors of his crew would be able to do so). The Northwest Passage, the dream of many explorers, would prove out of the question due to the Arctic ice.

It would be an infuriating problem that would remain for the next 400 years: how to get quickly across the thin strip of land connecting North and South America while dividing the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans?

The simple answer is: build a canal.

Ambition

Fewer things are more easily said than done. Still, the arduous work of creating artificial waterways for shipping would prove worth it, since transporting goods and passengers on one single ship is so much easier than having to unload, journey across land and load up again.

Humanity has done it for millennia, such as the Canal of the Pharaohs connecting the Nile to the Red Sea some two thousand years before the Suez Canal would be dug.

Other projects would prove far too lofty, such as the Corinth Canal that would have allowed sailors to cut through the middle of Greece rather than have to travel completely around it by the south. Despite consideration by kings, emperors and the Republic of Venice, it wouldn’t be until 1893 when those four miles of land were finally split to make today’s canal.

Cutting through Central America would be eight times that length at the very narrowest.

Nicaragua

Difficulties certainly wouldn’t stop people from dreaming, especially as the economic powerhouse of the United States to the north had a huge problem connecting its East Coast with its West.

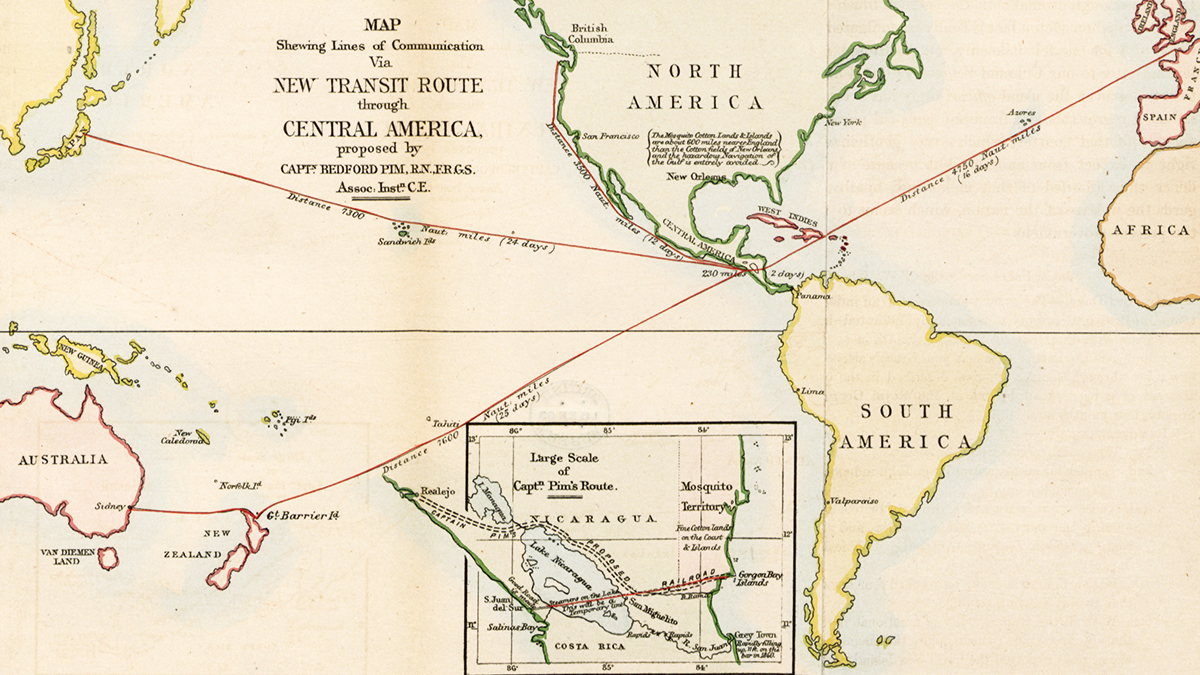

As early as 1826, Secretary of State Henry Clay was eager to make a canal happen, offering Congress an idea to dig a canal in the newly independent Federal Republic of Central America. Clay’s idea, along with the many who followed after him, was to cut across Nicaragua and tap into the wide waters of Lake Nicaragua for a ready supply to fill the necessary locks to raise and lower ships across the uneven shores of the Atlantic and Pacific.

Congress turned Clay down due to nervousness about the political stability of the area, which would soon break into a half-dozen countries.

Others thought they could use the instability to their advantage, such as filibusterer William Walker, but ultimately it was geological instability that prompted eyes to look elsewhere.

Panama

Panama seemingly was the more obvious choice for a canal being the shortest distance to cross. Charles V, Sir Thomas Browne and Thomas Jefferson each pointed out the suggestion to dig there.

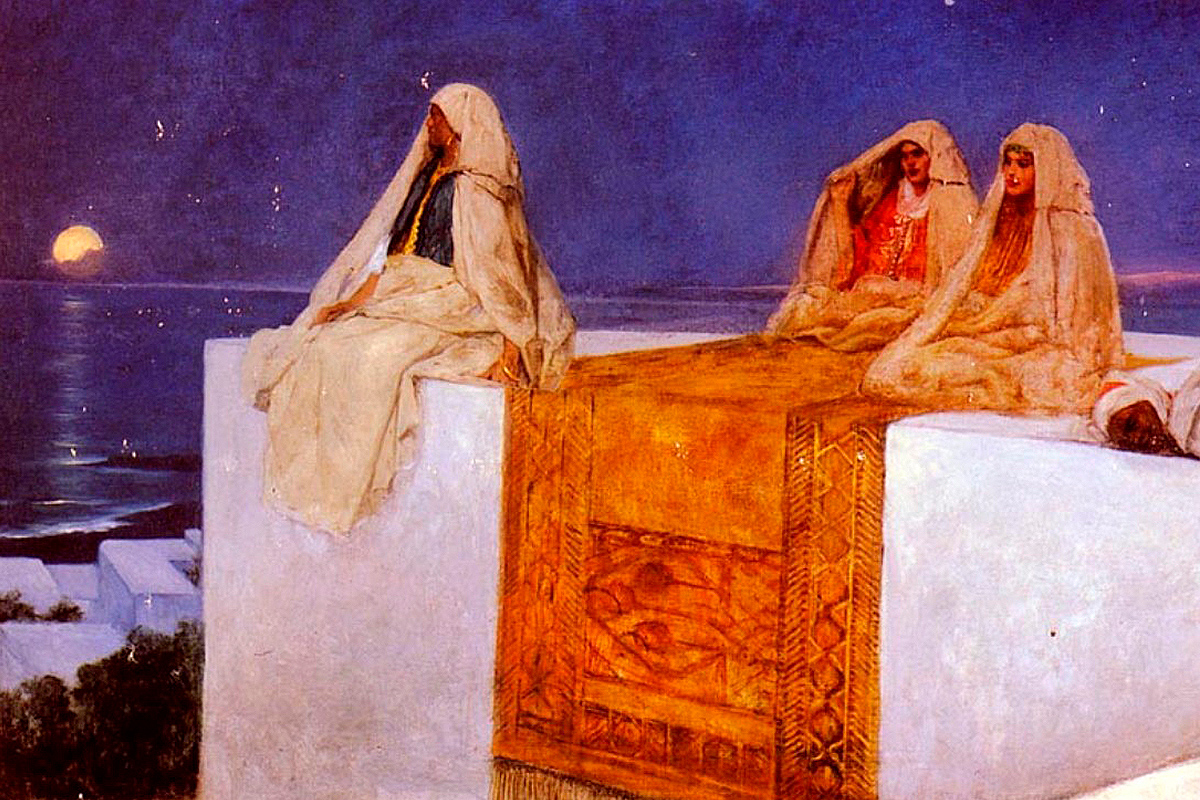

In the Darien Scheme of the 1690s, a Scottish expedition attempted to set up a colony for at least an overland route, but the mosquito-laden landscape proved too hostile.

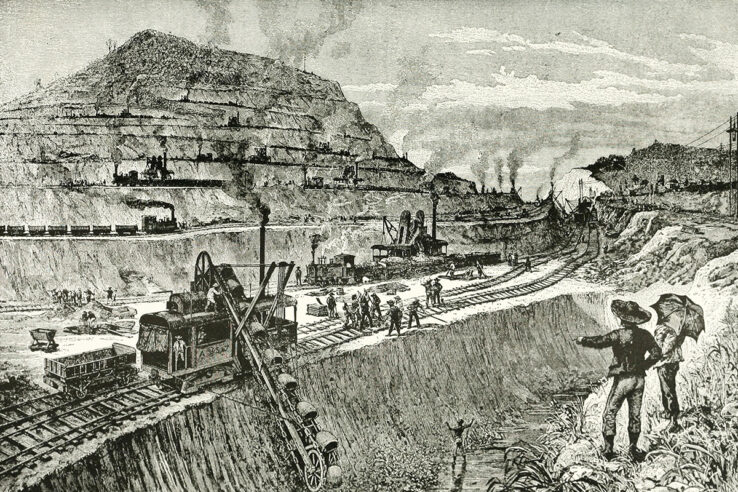

Political instability would interrupt American ambitions time and again with the region of Colombia changing governments several times through the 1800s. Great Britain announced plans in 1843, but soon gave up on them. Ferdinand de Lesseps, whose efforts championed the Suez Canal, led the French attempt in 1881, but that ended in defeat again at the hands of the harsh environment, costing the lives of 22,000 workers and the savings of 800,000 investors.

After the turn of the twentieth century, American efforts finally completed the canal. When the Senate of Colombia refused to ratify a treaty, President Theodore Roosevelt encouraged the success of Panamanian rebels, who were eager to agree to a canal for independence. The United States purchased what was left of the French effort and resumed digging.

Much of the work was spent not on the canal itself, but modernizing the canal zone to eliminate the mosquito population through spraying and irrigating landscape to wipe out their breeding grounds. Railroad engineer John Frank Stevens stated that digging a canal to sea level was “untenable” due to the floods of the rainy season. Instead, the Panama Canal would be built with the record-setting largest dam and man-made lake to create a system of locks.

In 1914, after ten years and $500 million (nearly $10,000,000,000 today), sea traffic could finally flow across Panama and cut off weeks of travel time.

Other ideas

But that is hardly the end of Atlantic-Pacific travel across the narrows of Central America. The idea for a Nicaraguan Canal still intrigues many, including the United States, who began doing surveys as early as 1916 just in case it proved better than Panama. An effort by China in 2012 is the latest to consider the route, although preferred travel up the San Juan River would bring Costa Rica into the political bargaining and countless environmentalists worry about damage to Lake Nicaragua.

What if other routes had been considered as well? The Isthmus of Tehuantepec is another narrow passage in southern Mexico, where political and environmental climates are more stable and a handy gap in the Sierra Madre mountain range rests to make digging all the easier. It would still be some 120 miles across, which would require an improbable amount of digging. As history showed, it was more probable to establish a railway for at least transporting light goods like mail, which was indeed established in 1907.

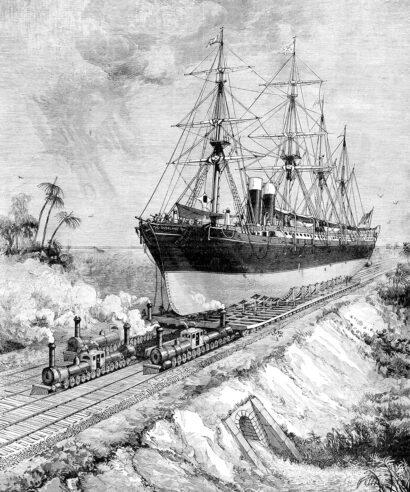

Less likely, but more impressive, is the notion of an interoceanic ship rail, proposed in the mid-1800s. Engineer James Eads envisioned four side-by-side railroads that would use locomotives to heft ships out of the ocean and pull them across land to be cast back into the sea on the other side.

Other routes may be considered south of today’s Panama Canal. The problem of the Darien Scheme and the French attempt at a canal had been biological with the onslaught of mosquito-borne illness. What if there had been a biological solution to that? In This Day in Alternate History, I took the point of departure of an invasive species, the Malaysian jumping spider, who spread rapidly by consuming the native mosquito population. Digging a Darien canal between the mountains in the Sierrania del Darien, damming the Chucunaque River and widening it to the Bay of San Miguel would be a monumental task, but perhaps achievable by a healthy, industrious populace, especially one upon whose success rested the economic viability of Scotland.

Even further south, the Atrato River flows roughly parallel with the west coast on its way down to the Gulf of Urbana at the northwest corner of Colombia. It would seemingly be a reasonable cut straight west and some engineering works on the river itself to make the Atlantic-Pacific passage. Indeed, in 1855 Manx engineer William Kennish suggested just that. Colombia, however, refused American interests in doing so. In 2016, environmental protection of the river basin was declared by the courts, ending any thoughts of a canal there.

While daydreaming of canals, why not connect one across the United States as well? The headwaters of the Yellowstone branch of the Missouri River (flowing east to the Mississippi and out to the Gulf of Mexico) and the headwaters of the Snake River (flowing west to the Pacific) come within a few miles of each other. Using nearby Lake Yellowstone as a reservoir for necessary locks, it could create a narrow connection point for light travel.

Of course, the cost of blasting, digging and construction would make the price of the Panama Canal itself look like a budgetary line item, not to mention the ecological damage to Yellowstone National Park.

This story was originally published by Sea Lion Press, the world’s first publishing house dedicated to alternate history.