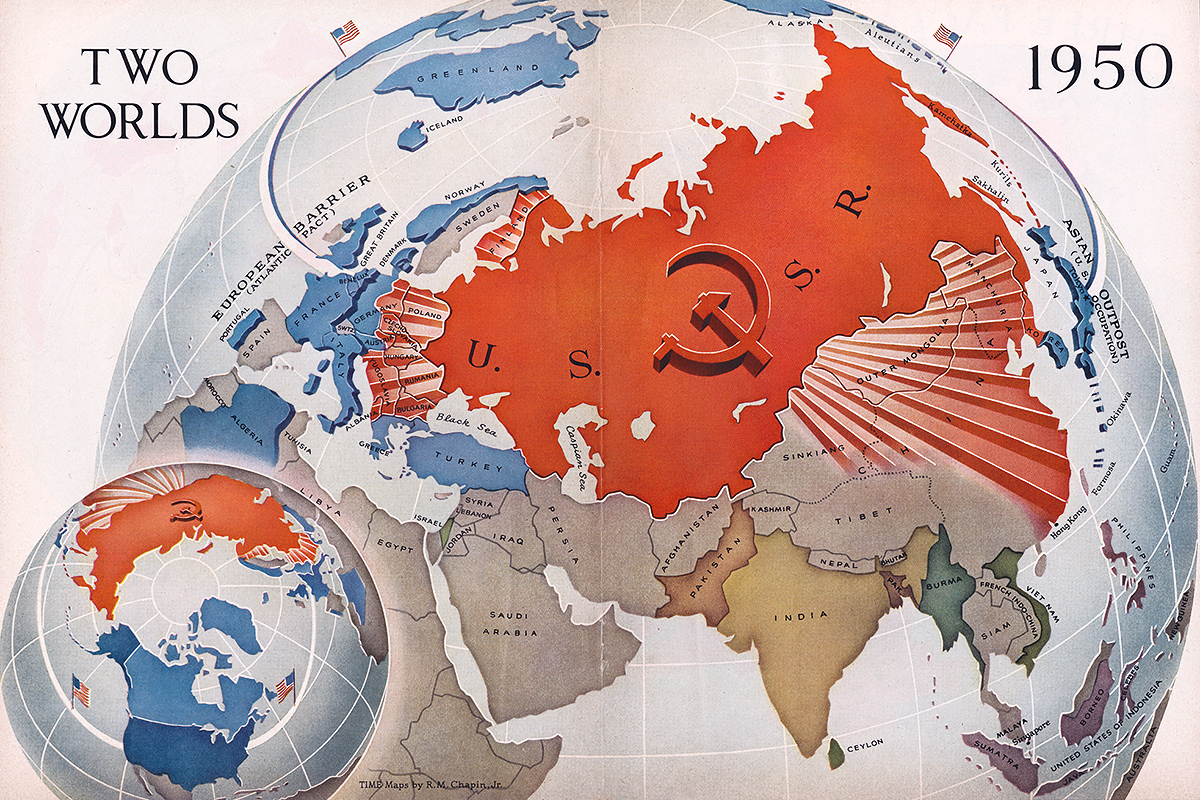

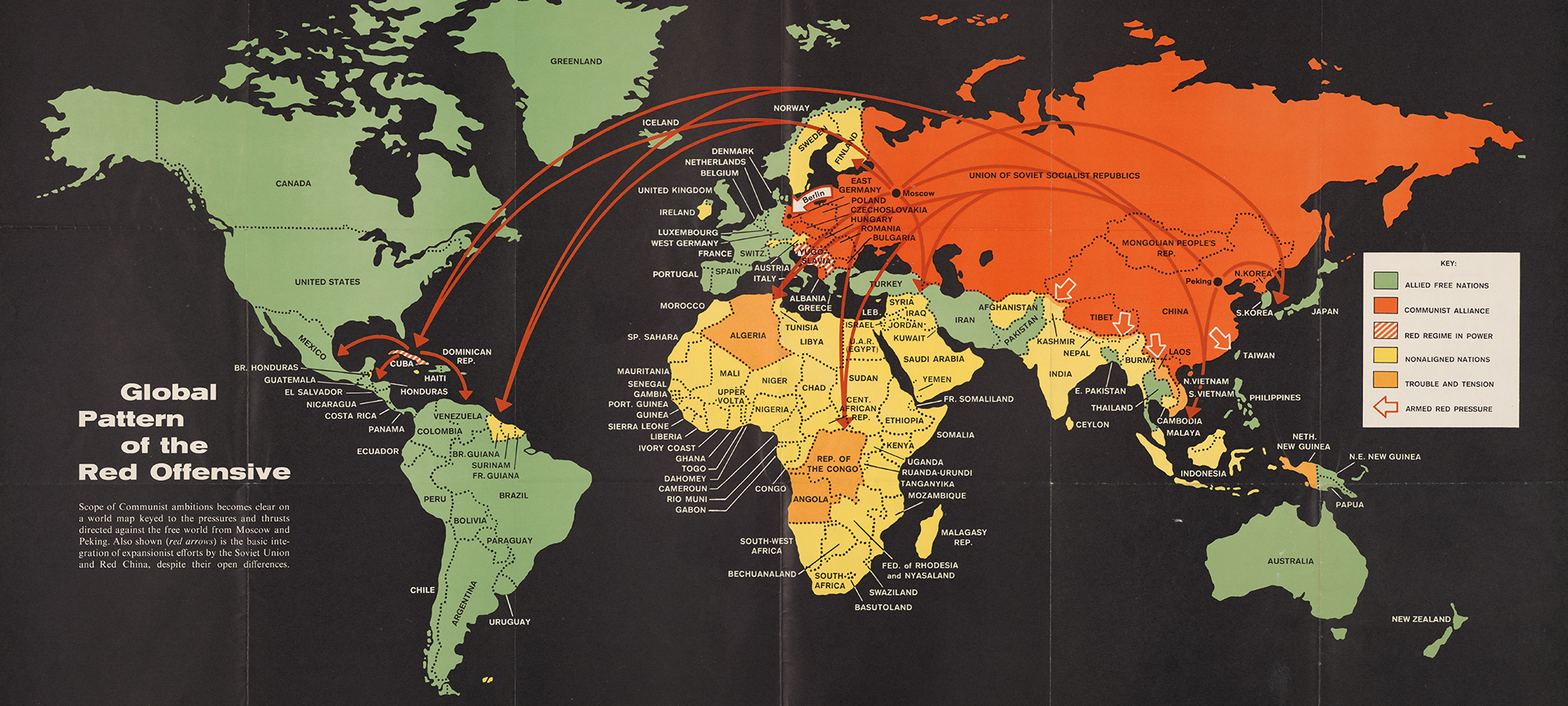

Most World War III scenarios start with a Soviet first strike, but it were the Western Allies who first planned to use nuclear weapons in Europe to offset the Red Army’s numerical superiority.

From Britain’s Operation Unthinkable to America’s Operation Dropshot, these plans help us imagine a land war in Europe fought only partially with atomic weapons.

When technology progressed in the 1960s — more and bigger atomic bombs, intercontinental ballistic missiles — NATO moved away from integrating nuclear weapons in its war planes. It envisaged either a conventional land war or mutually assured destruction with nothing in between.

The Soviets moved in the opposite direction. Joseph Stalin saw little use for nuclear weapons, but the West’s technological edge compelled his successors to integrate them more seriously in their offensive plans. It wasn’t until the 1980s that both sides abandoned the tactical use of nuclear weapons.

Operation Unthinkable

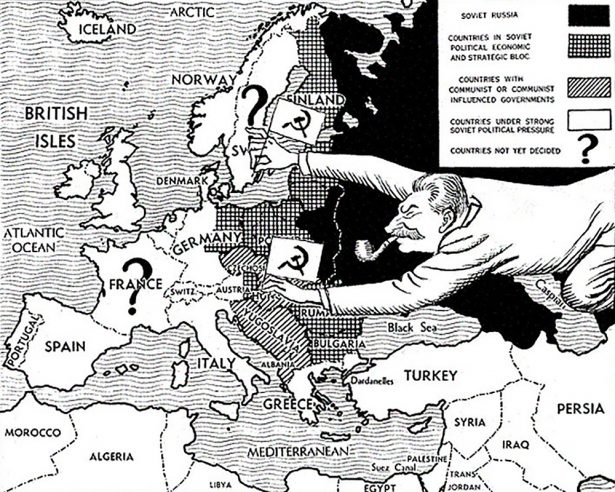

Before World War II was even over, Winston Churchill realized that Stalin wasn’t going to keep his promise to liberate Poland and the other nations of Eastern Europe. “People’s republics” were popping up everywhere in the Red Army’s wake as it descended on Berlin and Moscow’s hand in these communist transformations was all too obvious.

Churchill wrote to Anthony Eden, his foreign secretary, on May 4, 1945 that only “an early and speedy showdown” with the Soviet Union could still turn the tide of events. The alternative, he argued, was leaving France and the rest of Western Europe vulnerable to a Soviet invasion.

Churchill ordered General Hastings Ismay, who would later serve as NATO’s first secretary general, to plan a surprise attack on Red Army positions in Central and Eastern Europe. It was called Operation Unthinkable.

The idea was to strike in the middle of the Soviet lines, around Dresden, with 47 American and British divisions, roughly half of what the Western Allies had available at the time. Some 100,000 Wehrmacht soldiers were supposed to take part. The immediate objective was to free Poland, which was after all the reason Britain had gone to war in 1939.

Ismay considered the plan unfeasible and warned that, far from pushing the Red Army back, it might provoke the Soviet Union into launching an all-out war in Europe to defend itself.

The British estimated that Western troops would be outnumbered 2.5 to one. When the Americans withdrew some of their soldiers from Europe in order to support the planned invasion of Japan, the odds became — in Churchill’s words — “fanciful”.

The only way to make it work was to use nuclear weapons. That is the scenario Ian Chapman-Curry envisions on his excellent Almost History podcast.

Stalin, informed of Unthinkable by his spies, is ready for the attack when it happens. Marshal Georgy Zhukov easily drives the American and Commonwealth divisions into France, forcing them to fall back on the same Normandy beaches they had triumphantly landed on a year earlier.

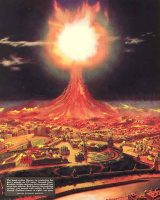

Awaiting the arrival of Prime Minister Clement Attlee and President Sam Rayburn — who, as speaker of the House, was first in line to succeed the disgraced Harry Truman — at a peace conference in Paris, Stalin dreams of reorganizing Europe and dismembering the British Empire — only to be interrupted by a nervous Lavrentiy Beria, who informs him that Moscow and Leningrad are gone. The Americans have dropped the bomb.

World War III has only just begun.

Operation Dropshot

America’s first plan for nuclear war was called Operation Dropshot. Drawn up in 1949 and declassified in 1977, it envisioned the Cold War going hot in 1957.

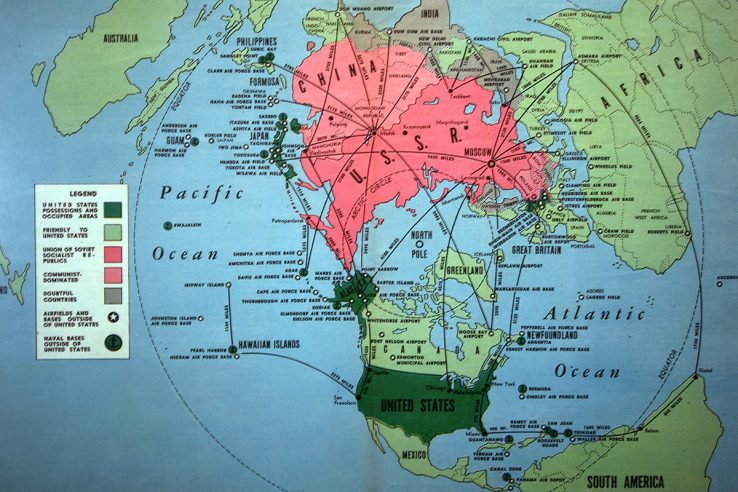

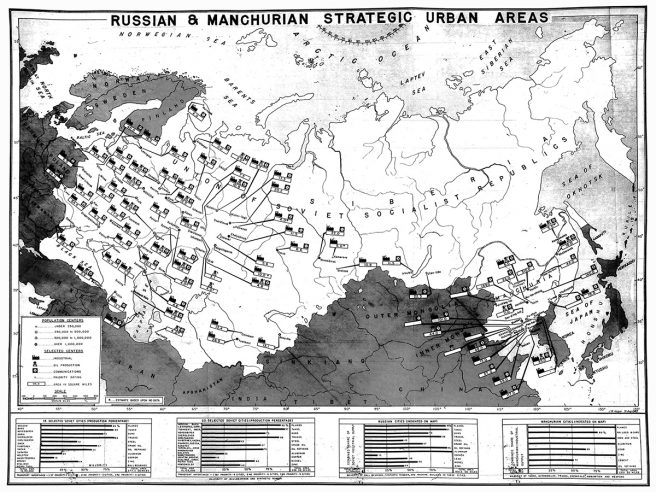

The plan, which can be read in its entirety here, proposed to use 300 nuclear bombs and 29,000 high explosives, launched from bases in Alaska, Okinawa, the Persian Gulf, the United Kingdom and the continental United States, against:

- Soviet facilities for the assembly and delivery of weapons of mass destruction;

- Lines of communication, supply bases and troop concentrations; and

- Electrical power, petroleum and steel targets.

Altogether, Dropshot identified 200 targets in 100 cities and towns that, if wiped out, would destroy 85 percent of the Soviet Union’s industrial capacity.

This initial wave of attacks would be followed up by air operations against naval targets, with an emphasis on reducing Soviet submarine capabilities, to achieve a sea blockade of the Soviet Union.

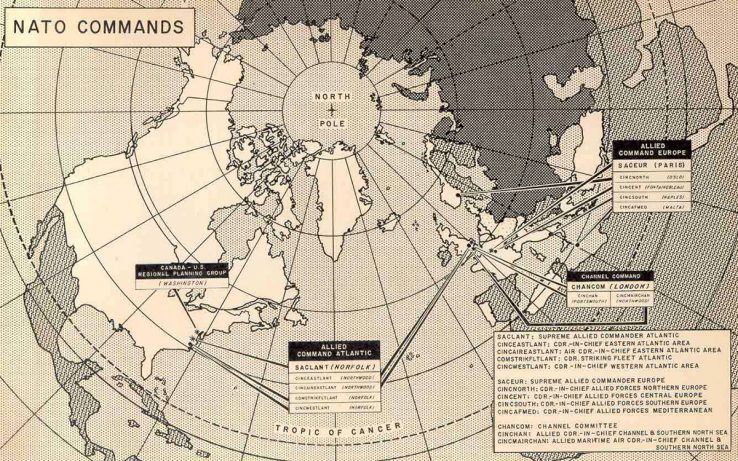

In Europe, NATO would establish a perimeter at the Rhine. This would become a recurring feature of Western war planning: Germany was essentially abandoned in a hypothetical World War III. The Americans calculated that sixty divisions would be needed to mount a defense. They had half.

In Italy, the West would make it stand on the banks of the Piave River. Sixteen divisions were needed there.

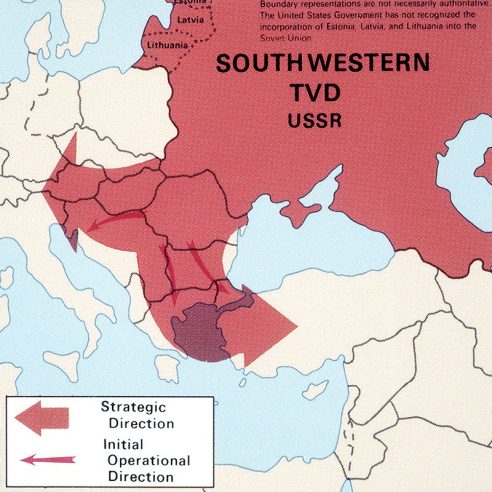

Control of the Middle East’s oil supplies was considered essential. Hence Dropshot called for a concentration of forces in southeast Turkey and the Tigris Valley to stave off a Soviet invasion.

If the Soviets did not capitulate, the plan argued for a major land offensive in Europe. It cautioned that the lessons of history, the vastness of Russia and the magnitude of the effort required, in terms of manpower and logistics, predicted “tremendous difficulties” ahead. A land war should only be carried out if “the bulk of Soviet war industries and communications systems have been destroyed and their oil production reduced to such a level that for all practical purposes their air forces have been grounded and their naval and ground forces have been rendered relatively immobile.”

The best route was across the Northern European Plain into Poland. This was the route invaders of Russia had historically taken, given its relatively flat terrain all the way to Moscow. It did have the disadvantage of long routes of advance, with the bulk of Warsaw Pact forces in opposition until the Soviet Union could be reached. But it was deemed more feasible than an amphibious invasion across the Baltic Sea or an attack from Scandinavia.

The only alternative was a strike at the heart of the Soviet Union from the Aegean Sea, the Turkish Straits, the Black Sea and Ukraine. This would still require a large amphibious landing, however, and have the disadvantages of long sea routes and long lines of communication.

What were the Soviets thinking?

Under Stalin, the Soviets did not plan to use atomic weapons in a war with the West, probably due to America’s massive nuclear superiority at the time. That changed in the 1960s, when the superpowers approximated nuclear parity.

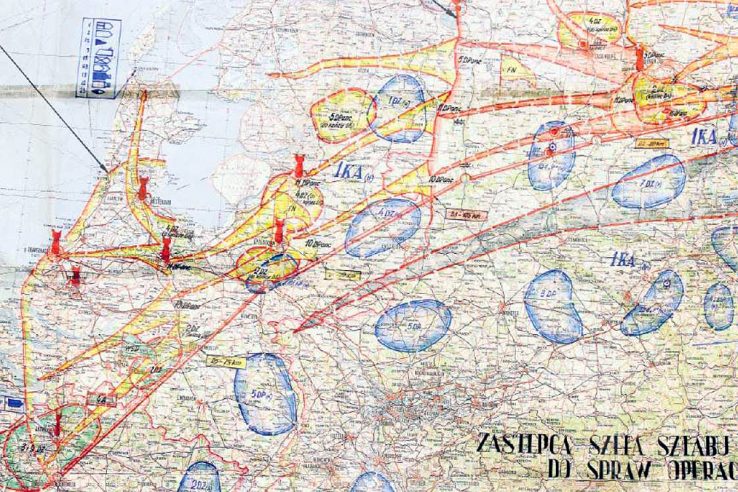

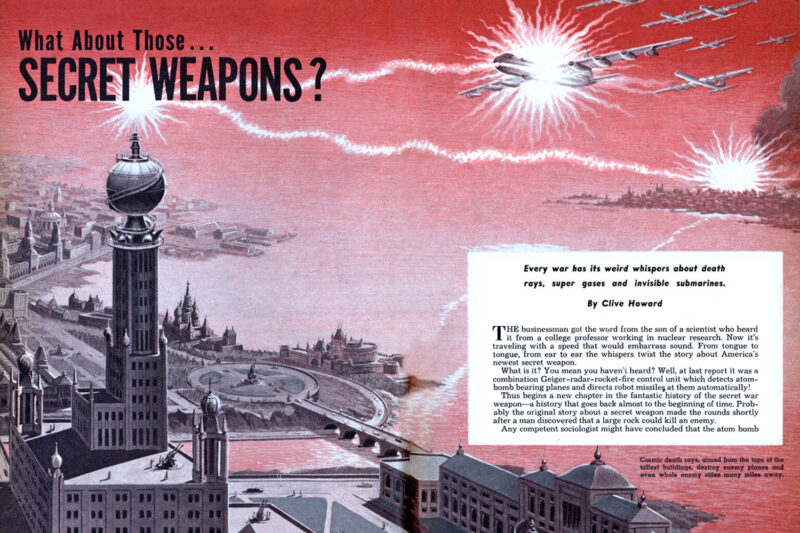

We know from 1964 and 1979 war planes, declassified by the post-Cold War governments of the Czech Republic and Poland, respectively, that the Warsaw Pact envisaged a generous use of nuclear weapons to clear the way for a ground invasion.

Zachary Keck has argued in The National Interest that this distinguished Soviet from NATO war planning. The Western allies never planned for a partly-nuclear conflict. From their point of view, World War III would be fought with either conventional or nuclear weapons. A combination was unthinkable.

The Soviets disagreed. Vojtech Mastny writes in “Planning for the Unplannable,” published in Taking Lyon on the Ninth Day? The 1964 Warsaw Pact Plan for a Nuclear War in Europe and Related Documents (2000), that their plans — at least as far as we know — did not consider the possibility that the Soviet Union might be paralyzed by retaliatory American nuclear strikes. Of course, that was exactly what the Americans claimed they would do.

Putting declassified Czech and Polish documents together with a 1987 American Defense Department study into a possible Soviet invasion of Europe gives us an idea of what World War III might have looked like if the Soviets had started it in 1950s or early 60s.

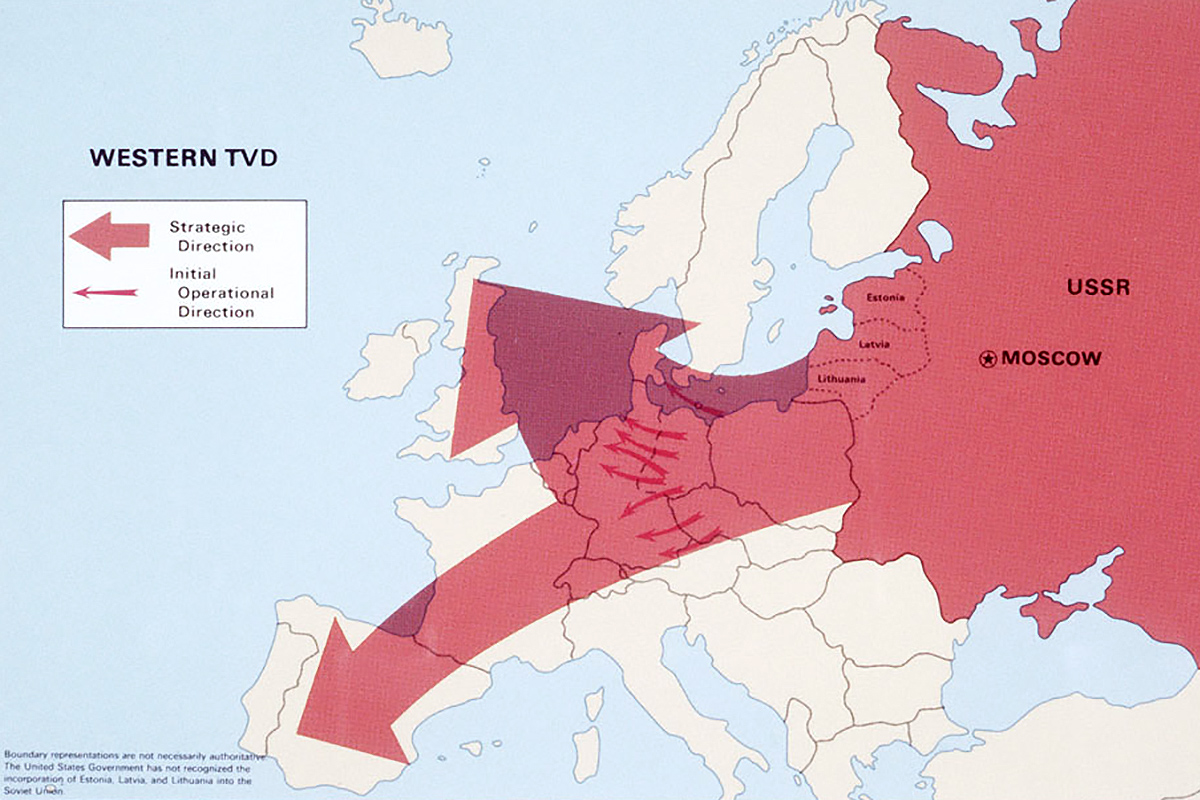

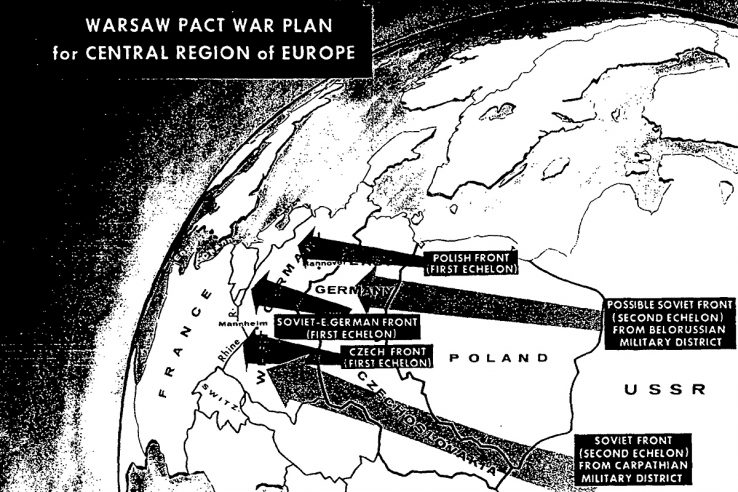

Two-pronged invasion

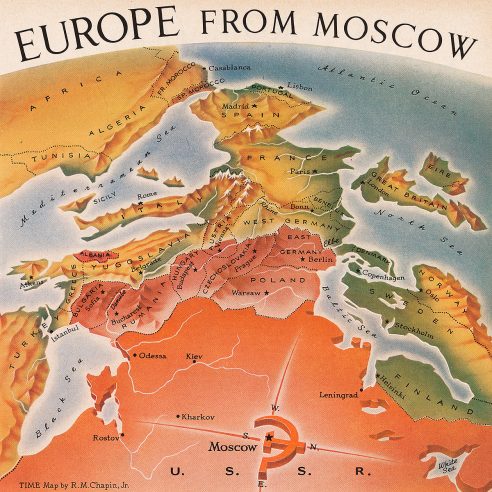

The main thrust of the Soviet invasion would go through Poland and then split in two: in the north, a march across the Northern European Plain into the Low Countries; in the south, a dive across Bavaria into France and Iberia.

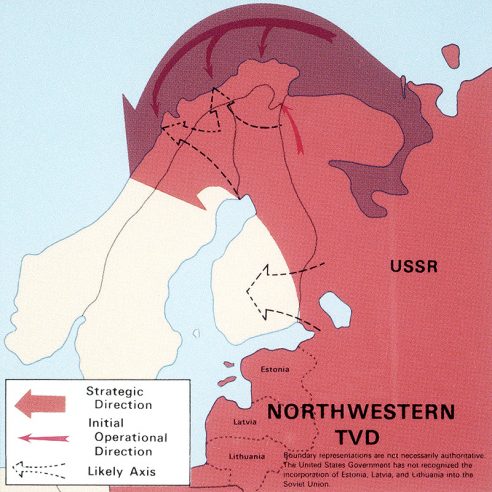

Secondary attacks would be carried out against Scandinavia and Southeastern Europe.

In the north, the goal would be to cut off neutral Finland from Norway and Sweden and then move Soviet forces down the coast toward Oslo and Stockholm. Only Norway was a member of NATO, but it would have been impractical for the Soviets to respect pro-Western Sweden’s neutrality.

In the south, neutral Austria and Tito’s Yugoslavia would similarly be treated as enemies in order to cut off Turkey from the fighting in Central Europe and force the Allies to retreat into France. (Forty years earlier, Dropshot had predicted that Yugoslavia would side with the Soviets.)

Of the two, the Balkan offensive was the more important. Without it, a Soviet army making its way across southern Germany risked being encircled and trapped in case the Allies managed to push back the northern invading force.

Poland, which had the second-largest army in the Warsaw Pact, would lead the occupation of the Low Countries. Amsterdam, Antwerp, Brussels, Copenhagen, Hamburg and Hanover would all be nuked to clear the way for the invasion.

By 1979, the plan was to spare nuclear-armed Britain and France in hopes that they might be persuaded to sit out the war. Hungarian forces would capture what was left of Vienna. Czechoslovak soldiers would be sent into post-atomic Munich, Nuremberg and Stuttgart. The offensive would halt at the Rhine.

A similar plan is presented by General Orlov in the 1983 James Bond movie Octopussy.

The 1964 plan did call for an advance into France, led by the Czechoslovaks.

Having taken Lyon in the south — and presumably having lost many troops to radiation poisoning — Soviet reinforcements would arrive from the Carpathian Military District to push all the way down the Pyrenees.

The idea was to accomplish this within seven to nine days, which seems ambitious. War is Boring points out that the Nazi blitzkrieg through France in May 1940 astounded the world by advancing 35 miles per day.

To meet their deadline, the East Bloc armies would have needed to double this rate of advance to some seventy miles per day, all while fighting well-trained defenders armed with advanced weapons.

Where to make a stand?

For the Western alliance, the question would be where to make a stand?

Back in 1949, Dropshot had ruled out trying to hold West Germany. The absence of natural defenses made such an attempt hopeless. Better to hold what it called the Rhine-Alps-Piave Line: the best natural defense line in Western Europe and the most easterly line feasible of defense. It would retain the bulk of European manpower and industry under NATO control.

If that failed, Dropshot recommended falling back on the Rhine-French-Italian Border Line. It would mean giving up mainland Italy and Sicily and with it airbases for operations against the Balkans.

The Allies could also make a stand in the Apennines, just like the Germans and their Italian allies had done in World War II. It had the advantage of strong natural defenses, and it would retain some Italian bases for NATO, but it would mean giving up the north of Italy, which is where most of the country’s industries were (and still are).

Dropshot considered attempting to hold the Cotentin or Brittany Peninsula as a bridgehead for operations in Europe, but cautioned that neither had strong natural defenses.

Withdrawing behind the Pyrenees was preferable from a defensive point of view, and would permit control of the Strait of Gibraltar and the western Mediterranean, but it would be much harder to launch a counterattack from Spain. (Not to mention the political awkwardness of relying on the fascist regime of Francisco Franco.)

Holding the Nordic states was considered futile, given the difficulty of mounting a counterattack on Russia from the north.

Early-Cold War planning thus concentrated on holding the Rhine, with a defense of West Germany only becoming feasible in the 1960s and 70s, when NATO caught up with the Warsaw Pact in terms of conventional-weapons strength.

8 Comments

Add YoursFascinating as usual, Nick! I love the ‘OCTOPUSSY’ clip. Steven Berkoff (a Briton) and Walter Gotell (a German) made excellent Soviet commanders!

I am still surprised that somehow we avoided a hot war given the circumstances.

Rather bizarre that Churchill considered a plan to liberate Poland given he had clearly agreed to allocate Romania and Bulgaria to Stalin in the Percentages Agreement of October 1944 and it was assumed that the USSR would have a free hand in Poland.

I don’t think Churchill was ever fond of that agreement. Nor, of course, was it legal. His fear was that the Soviets wouldn’t stop there and keep on pushing west.

Given that Cuba had been equipped by the Soviets not only with ballistic missiles but also tactical nuclear weapons in 1962, it seems that the most likely use of tactical nuclear weapons would have been to counter a new US invasion of the island. The focus has tended to be on the missiles, but it might have been the smaller weapons, under the control of local commanders that might have been used, irradiating a slice of the Caribbean.

I noticed that the article makes no mention of the Pincher war plans that were the basis of American warplanning between 1946-49. These observed that even holding onto Western Europe and the Middle East north and east of Israel-Palestine was impossible, since the Western Allies only had about the equivalent of 4 divisions against a Soviet force that consisted of, at best, 32 divisions and, at worst, more then 100. The plan was essentially to forfeit Western Europe and hope Britain could be held for long enough for the atom bomb to be brought to bear.

Thanks for your comment!

Was that different from Dropshot? Because it made pretty much the same argument when it came to where to hold the line.

Good article. I feel obligated to note that (and I’ve seen translated primary sources) by the late 1960s, the Soviets, even while considering them implausible, had laid out entirely conventional war plans.