Octopuses are a popular trope in political art. They came in vogue in the 1870s, when Frederick W. Rose depicted Russia as a giant octopus lording over Eastern Europe. The sea monster was quickly given to Germany when it posed a bigger threat to peace in Europe. During the early Cold War, it was Russia’s turn again. The octopus was the perfect metaphor for spreading communism.

Here is a selection of the best and worst tentacled sea creatures.

Russian octopus

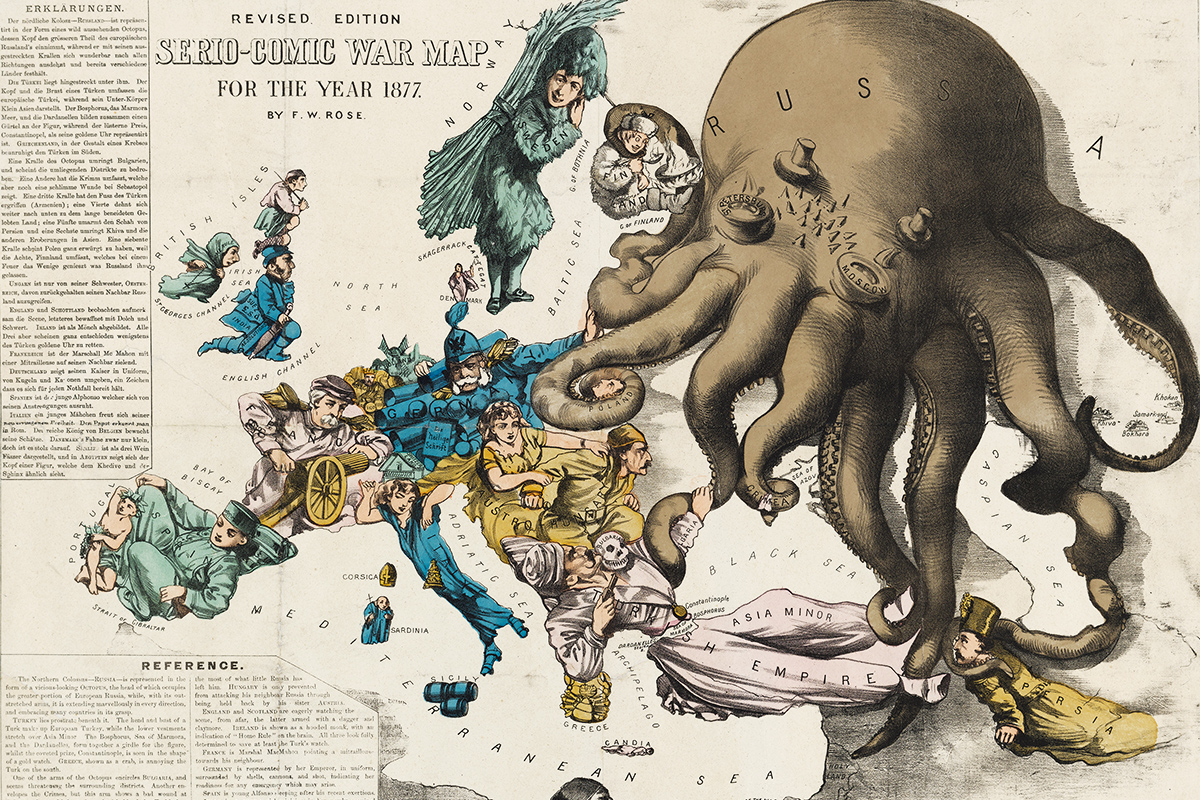

Britain’s Fred Rose was the first to depict Russia not as a bear but as an octopus. His Serio-Comic War Map, which would be revised and translated into various European languages, appeared in March 1877, two months after Russia had attacked the Ottoman Empire in response to its massacre of Christians in Bulgaria (represented on the map by a skull).

Rose shows the giant Russian octopus strangling Persia and Poland, holding Finland in its grasp and tussling with Turkey.

British politics was divided at the time between William Gladstone’s anti-Turkish Liberals, who were apologetic of Russia, and the Russophobe Conservatives, who called for a pact with the Ottomans to block Russian expansion. Rose’s cartoon helped sway public opinion in their favor.

Tentacles into Asia

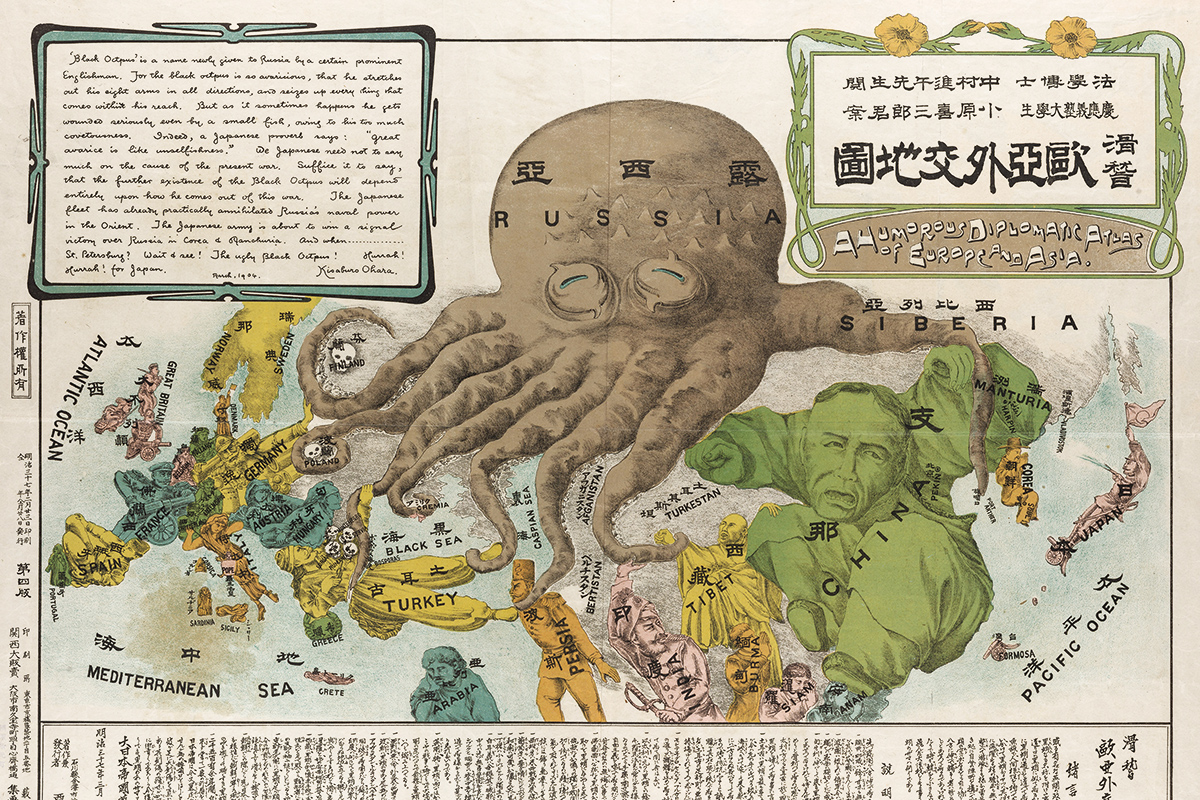

One of the first artists to imitate Rose was Japan’s Kisaburō Ohara. This cartoon, from the time of the Russo-Japanese War, shows Russia’s tentacles stretching into Asia. Of note is the rightmost tentacle, which touches Port Arthur: the site of Japan’s 1904 attack on the Russian Fleet.

The map was made to persuade Britain, then the world’s premier naval power, to stay out of the war.

The devilfish in Egyptian waters

The late nineteenth century was also the high-water mark of British imperialism. This 1888 cartoon, published in Punch, shows John Bull, the personification of the United Kingdom, dabbling in Egyptian waters.

“He is a curious mixture of the lion, mule and octopus,” gobbling up territories along the route to India: Gibraltar, the Cape, Malta, Cyprus and the recently inaugurated Suez Canal.

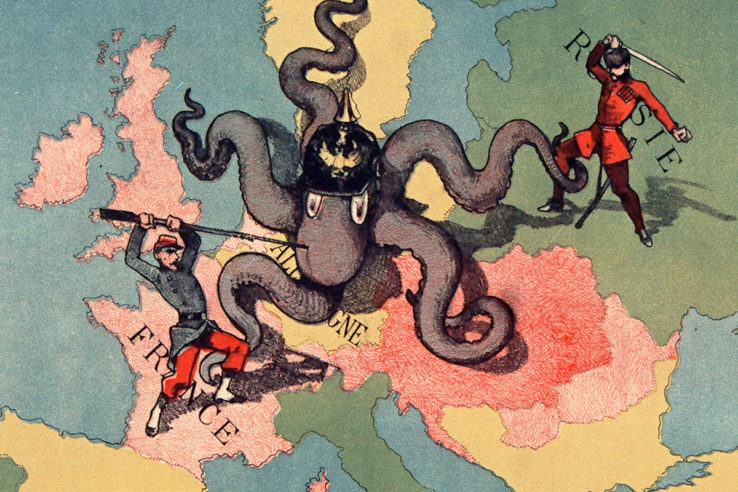

Revanche

Prussia, and later Germany, became an octopus favorite in French propaganda.

This cover of the revanchist French public-affairs magazine La Revanche depicts France and Russia slaying the German octopus in 1886, fifteen years after France lost Alsace and the Moselle department of Lorraine in the War of 1870. France and Russia would formalize an anti-German alliance five years later.

Twins

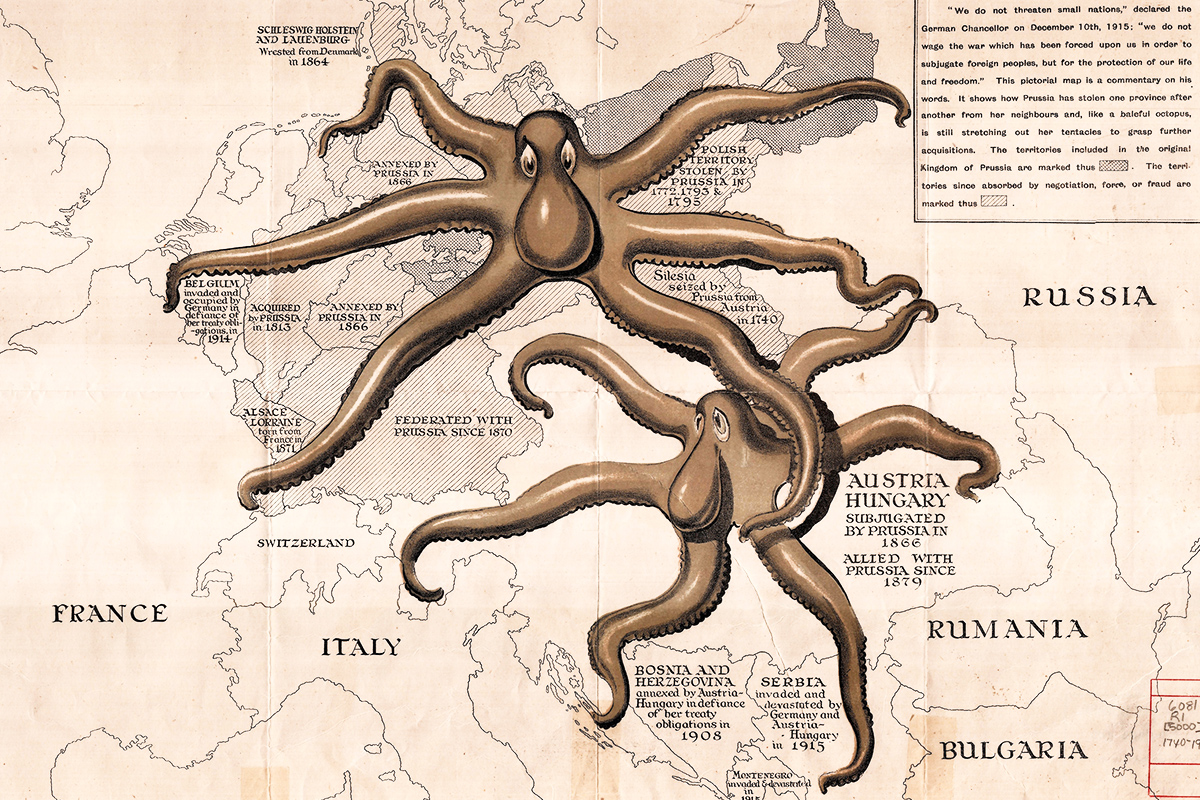

This 1915 British map — also translated into other languages — makes a mockery of Germany’s promise not wage war “in order to subjugate foreign peoples” by highlighting the lands it and Austria had annexed over the centuries.

It simplifies Prussia’s territorial expansion, however, and leaves out the historical context. Bavaria, for example, freely merged with Prussia to form the German Empire in 1871. The map also neglects to mention the role Britain’s ally Russia played in the partition of Poland.

Prussian expansion

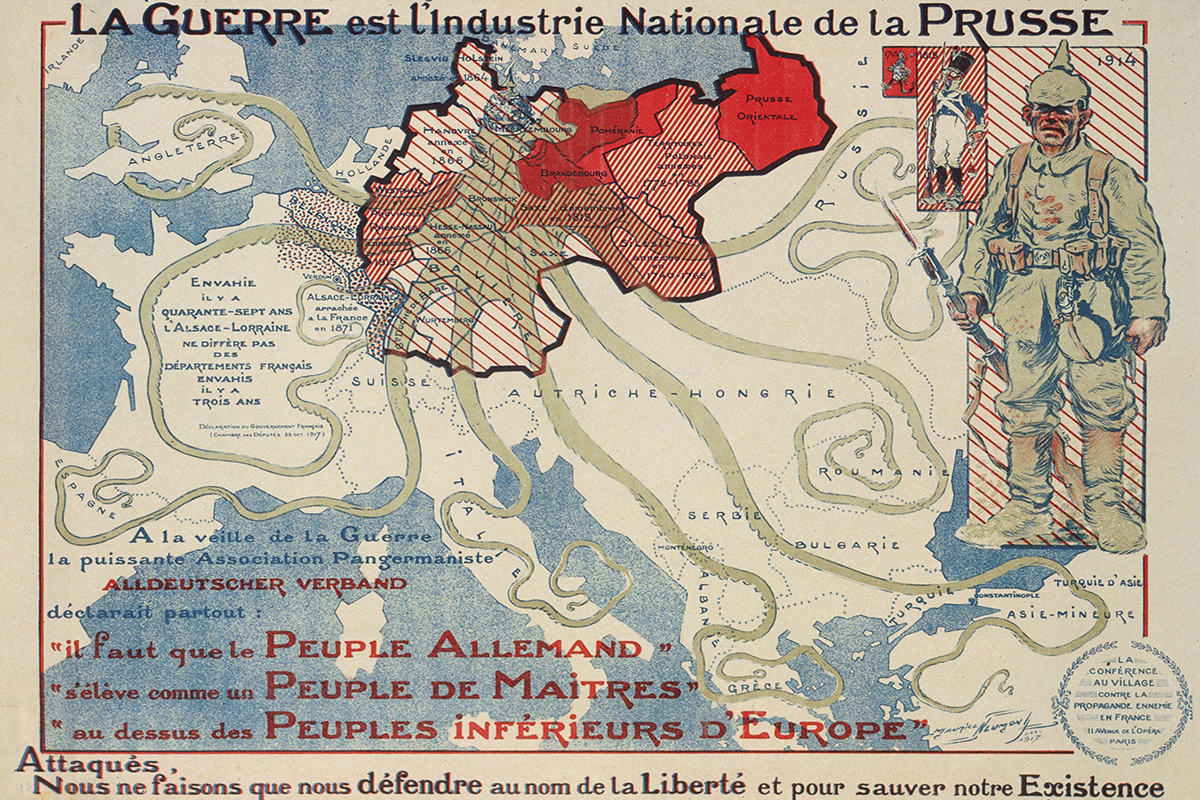

A French version of the above. Look closely and you’ll see the octopus wearing a Pickelhaube in the middle.

Maurice Neumont, the illustrator, quotes various French politicians who warned against Prussian expansionism. The Hunnish soldier represents the size of Germany’s army compared to Revolutionary France’s a century earlier. Perhaps a fairer comparison would have been with the French army of 1914, which had four million men under arms against 4.5 million for the Germans.

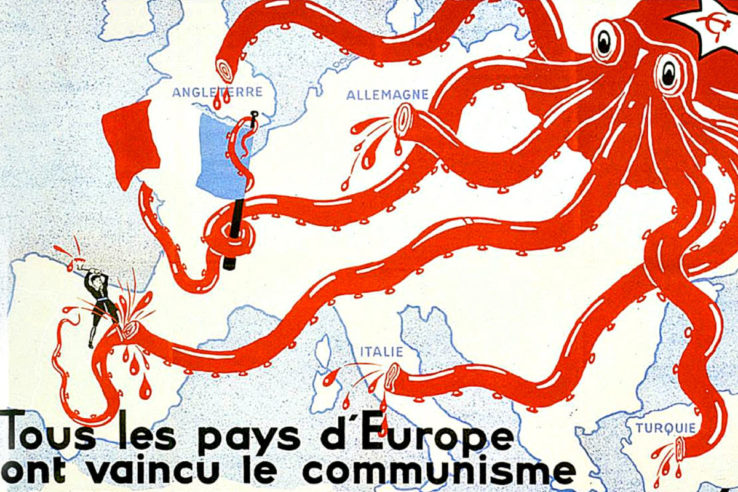

Urging the French to resist

This 1936 or 1937 French anti-communist propaganda poster was one of the first that depicted Soviet Russia as an octopus.

It argues that the whole of Europe is fighting communism. Notice that the British, Germans, Italians and Turks have all cut off one of the octopus’ arms. The Spanish Nationalists are in the process of doing the same. (The Republican side in the Spanish Civil War was supported by the Soviet Union, although it was only partially communist.)

The French, by contrast, are supposedly allowing the communist creature to strangle their flag.

Stalin the sea monster

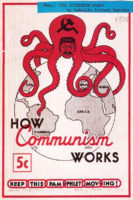

This American anti-communist pamphlet, produced by the Catholic Library Service in 1938, takes the octopus metaphor one step further by depicting Soviet leader Joseph Stalin himself as the sea creature.

One of his tentacles is curling around Spain, where the Civil War is still raging. Another extends to North America — the suggestion, of course, being that the ungodly red menace was reaching for the United States.

Bloodthirsty Churchill

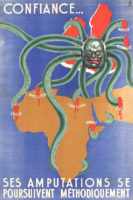

Fascists returned the favor in 1941 or 1942 by depicting Britain’s wartime prime minister, Winston Churchill, as an octopus.

His tentacles are seen reaching around Africa and the Middle East. The amputations at Dakar, Mers El Kébir, Egypt, Libya and Syria indicate Axis resistance to British imperialism.

The idea was to convince the French their real enemy was Britain, even though the Nazis were occupying their homeland. The locations mentioned were sites of Allied military action against Nazi-allied Vichy France. Britain’s attack on the French fleet at Mers El Kébir in particular had caused many French casualties.

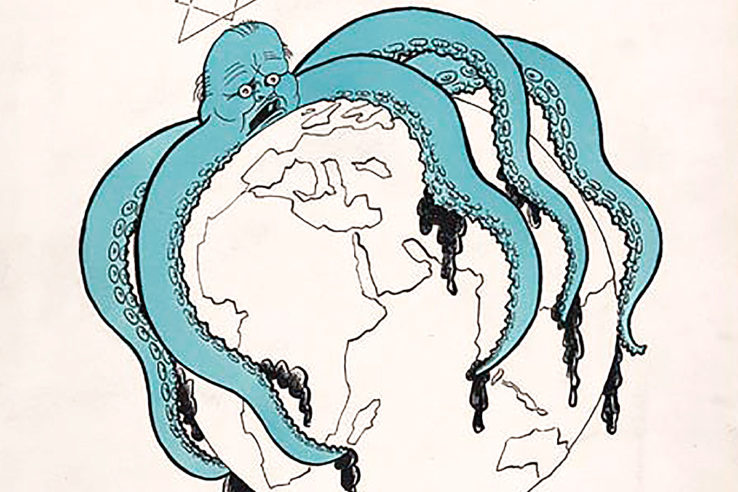

British-Zionist conspiracy

This antisemitic German cartoon, published somewhere between 1935 and 1943, similarly depicts Churchill as an octopus but with a Star of David over his head, linking British imperialism to an imaginary global Jewish conspiracy.

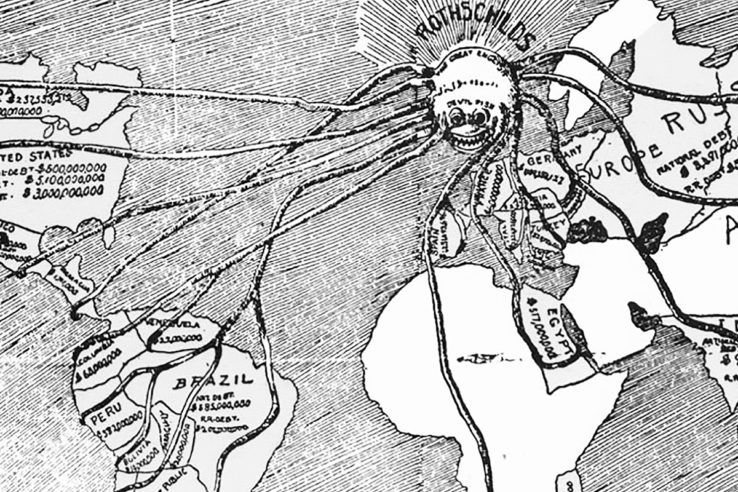

Rothschild octopus

The idea of Jewish money interests controlling British policy was an old one. In a 1894 pamphlet that argued for the introduction of a mixed gold and silver standard, William Hope Harvey had depicted the Rothschild banking family as synonymous with England. Their tentacles stretch all over the world.

Standard Oil

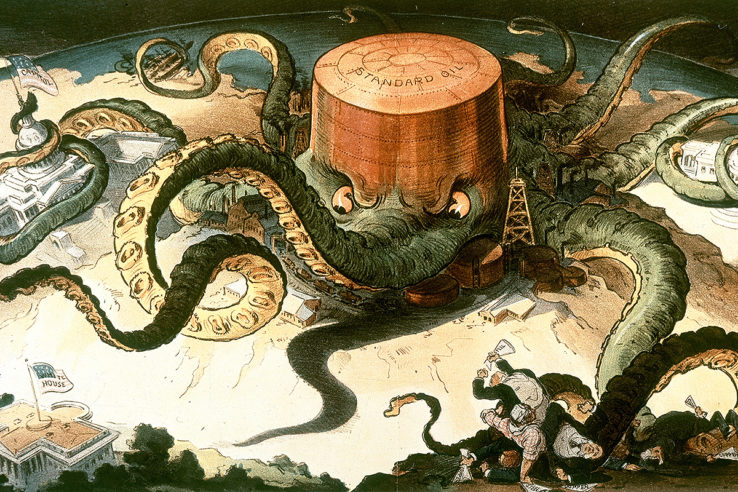

The most famous octopus cartoon must be this 1904 depiction of John Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. Notice that its arms are wrapped around not just the United States Congress and a state house but also the cooper, steel and shipping industries. The next target is the White House.

Anti-monopolist cartoons like these helped the trustbusting Theodore Roosevelt prevail in the presidential election that year.

Japan’s unwelcome embrace

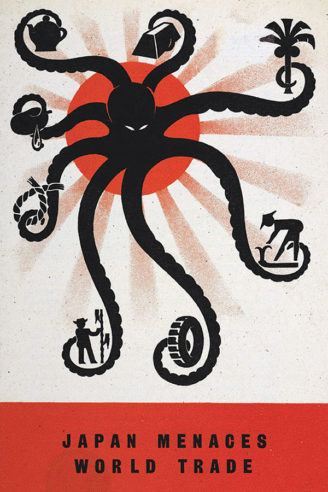

Japan did not escape depiction as an octopus in Allied propaganda.

A British poster argued the other island power menaced world trade by showing its tentacles wrapped around commodities found across East and Southeast Asia.

A 1944 Dutch poster called for the liberation of the East Indies from Japan’s unwelcome embrace. Although “liberation” meant return to Dutch colonial rule.

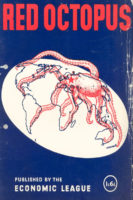

Red Octopus returns

The red octopus returned after the Second World War, when the capitalist West and the communist East fell out once more.

This image comes from the cover of a 1950 leaflet spread by the pro-business Economic League in the United Kingdom. It suggests communism is about to devour the whole world.

Recognize the danger

Only slightly less threatening, this 1949 election poster for Austria’s conservative People’s Party shows communism spreading its influence westward into Europe. It urges voters to “recognize the danger” of Soviet ideology.

Like Germany, Austria was occupied by the victorious Allies at the time. The Soviets controlled what would become the states of Burgenland and Lower Austria. Only after the country professed neutrality in 1955 did Western and Soviet troops pull out.

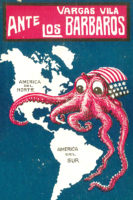

American imperialism

Leftists employed the octopus trope too.

The Colombian writer José María Vargas Vila, for example, depicted the United States as a hungry sea monster on the cover of his Ante Los Bárbaros (“Facing the Barbarians,” 1930), clutching the island of Cuba, then under pro-American rule, and eying Central America.

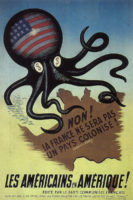

“France will not be a colony”

The French Communists had the same idea. Notice the dollar signs in the American octopus’ eyes in this 1950s poster.

The text reads: “No! France will not be a colonized country!” The French were anxious at the time about becoming an American dependency.

2 Comments

Add YoursWonderful illustrations

i liek ocopus