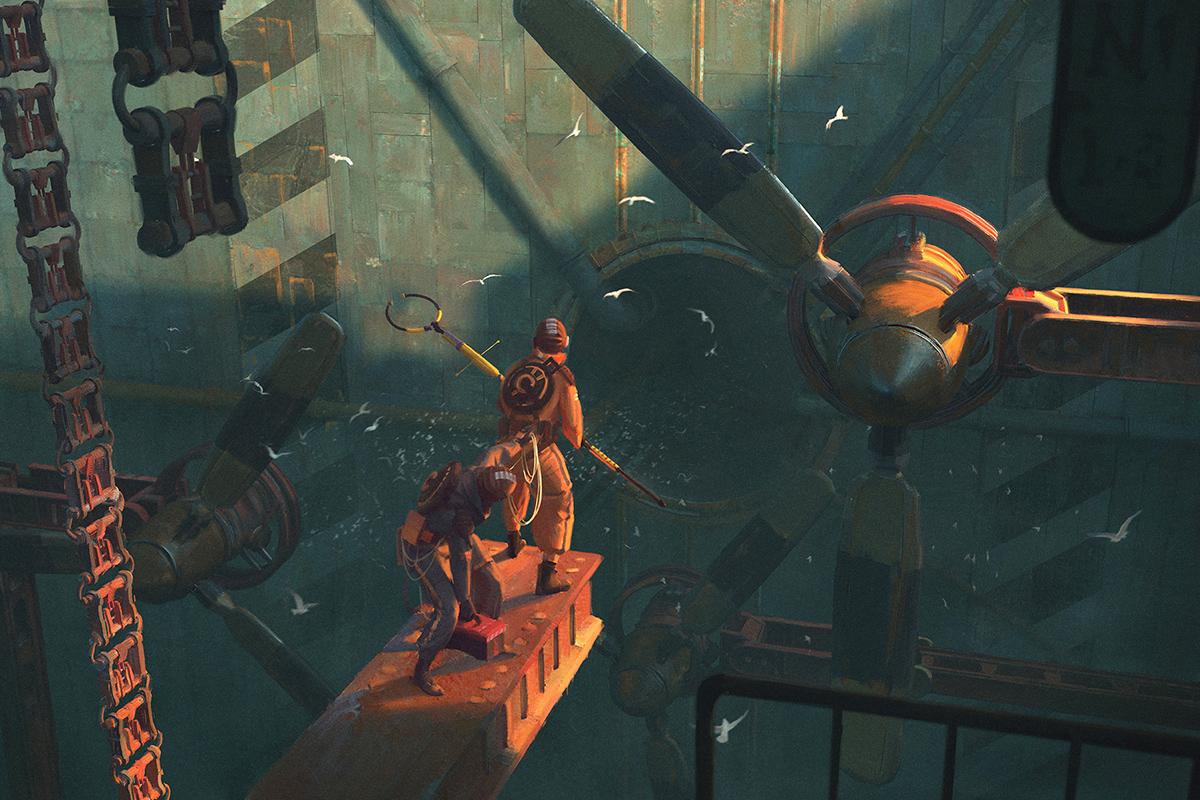

Christine Folch wonders in The Atlantic why fantasy and science-fiction are so popular in the West. Her explanation is applicable to steampunk.

Folch cites nineteenth-century German sociologist Max Weber, who argued that economic and political progress had “disenchanted” Western societies.

Weber posited that because of modern science, a rise in secularism, an impersonal market economy and government administered through bureaucracies rather than bonds of loyalty, Western societies perceived the world as knowably rational and systematic, leading to a widespread loss of a sense of wonder and magic. Because reality is composed of processes that can be identified with a powerful-enough microscope or calculated with a fast-enough computer, so Weber’s notion of disenchantment goes, there is no place for mystery.

But people like mystery. “And so we turn to science-fiction and fantasy in an attempt to reenchant the world.”

Similarly, steampunk harkens back to an era when adventure and wonder were, in our twenty-first-century reimagination of it anyway, commonplace.

2 Comments

Add YoursFor me reading is a lot about reenchantment and escapism. I know I love urban fantasy and mythic fiction because of the idea that there is still magic in the world, and I love Steampunk because I can escape to a world with manners and beautiful clothes, yet more social and gender awareness, magic and invention than the real past.

People like mystery. “And so we turn to science fiction and fantasy in an attempt to reenchant the world.” Or, alternatively, we might turn to and explore Shamanism, study African and Oceanic arts and cultures, which all recognize the inherent mystery and unknowability of the world we live in. Do we really need fantasy and science fiction magazines when traditional societies remind us that our way is not the only way? A child raised in the Andes to believe that a mountain is a protective deity will have a relationship with the natural world profoundly different from that of a youth brought up in America to believe that a mountain is an inert mass of rock ready to be mined.

Traditional societies remind us that there are indeed alternatives, other ways of orientating human beings in social , spiritual and ecological space. Maybe in Weber’s eurocentric world there is no place for mystery – but in my world there is much evidence of things unseen, of inner and outer worlds still left unexplored. The mythology of the Barasana and Makuna people is better then any fantasy magazine – and points us all to the fact that the path Western societies have taken is not the only one available.