By the 1920s, the world was still a big place. While nearly every conceivable corner of the Earth had been explored and mapped by now, it was getting there in the fastest or most efficient way that was getting more attention.

Airplanes had just began making their entry in the travel scene and indeed revolutionized the way far-flung destinations could be reached — at least for those who could afford the steep fares of air travel.

Simultaneously, an ever-increasing number of passenger liners served an ever-increasing number of ports, and bigger ships combined with fierce competition meant the prices for ocean crossing were kept reasonably low.

However amazing all these developments were, one cannot escape the notion that they ultimately served but one purpose: to avoid having to travel over land at all costs.

The nightmare of overland travel

There were perfectly good reasons for wanting to do so, naturally. Roads were bad enough within the confines of the civilized world and more oft than not became entirely non-existent the farther one ventured away.

Cars at the time were small, uncomfortable, prone to breaking down and the logistics of overland travel were nightmare-inducing.

For example: fuel could only reliably be purchased in larger cities. In smaller towns, it was available only sporadically. Outside the towns, it could be virtually impossible to fill up.

Add to that the fact that most cars were only able to get a mileage of around 10 mpg and it becomes easy to see why not many long trips were made by car back then.

Perhaps even more daunting than that was the political climate in some regions and the apparent lack of politics in some other. Some countries could be difficult to traverse because of endless bureaucracy or just plain hostile foreign relations while others had so precious little actual control over what was happening within their borders that roving bands of bandits were commonplace.

Who in his right mind would willingly plunge himself into such madness then?

Well, typically such people fall under two broad categories. There are the true adventurers, who would do it “because it can be done,” and there are the military types who would do it “because it must be done.”

This story has plenty of both.

French empire in Africa

So why did a French team decide to cross the Sahara by car in the first place?

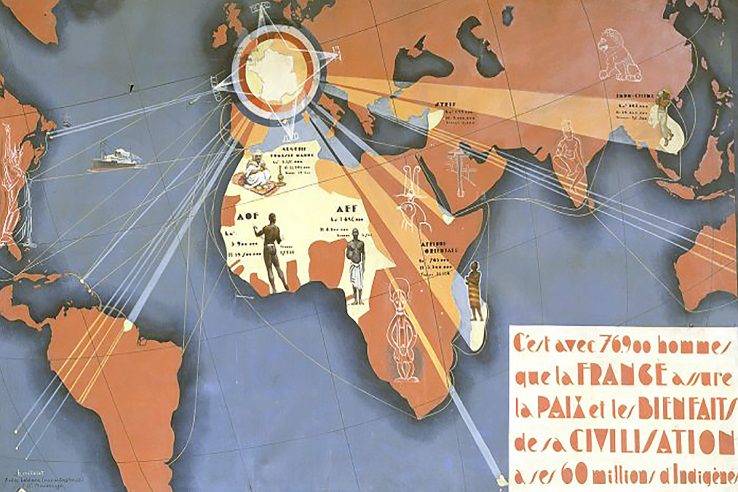

To answer this question, it is important to realize that by the early twentieth century, colonialism was still very much the name of the game. All of Europe’s more influential countries maintained a large number of overseas territories.

The French Colonial Empire of the day spread out over much of Northern and Western Africa. Nearly all of the Sahara Desert was claimed by the French, with many important colonies laying just south of the desert.

When recovering from the First World War, the idea of a quick and safe overland passage between France and the Sub-Saharan colonies suddenly became attractive. French industry desperately needed the resources. Likewise, settlers who were previously nearly cut off from the homeland due to its preoccupation with the war were jubilant about the idea of new supplies. When the support of the military and scientific communities was won, the expedition could start.

The expedition

The car that would make this journey possible was the Citroën Kégresse, one of the first successful half-track vehicles.

The tracks, invented by Adolphe Kégresse in 1921, were continuous rubber tracks and allowed the vehicles a road speed of 45 km/h (28 mph) and an off-road agility previously unseen in motor vehicles.

Citroën quickly realized the importance of the expedition as a marketing tool. Indeed, they had been after securing military contracts for their vehicle and the expedition would be the perfect showcase for its qualities. Citroën offered to sponsor the expedition with five vehicles, provided that the expedition be led under military supervision.

This military supervision came in the form of Georges-Marie Haardt and Louis Audouin-Dubreuil, experienced officers in the French military. The rest of the team was made up of a photographer, a geographer, an army mechanic and five more officers for a total crew of ten.

The five vehicles were given names by their crews. Translated, the cars were named; Golden Beetle, Silver Crescent, Flying Tortoise, Ox of Apis and Crawling Caterpillar.

From Algiers to Timbuktu

The expedition left Algiers on December 18, 1922. The caravan traveled between forts and towns to replenish food, water and fuel supplies along the way. Their route went from Algiers to El Golea, In Salah, Arak, Tamanrasset, Tin Zaovaten, Bourem, Gao, Niamey and finally Timbuktu. They covered a total distance of 3,120 kilometers (1,950 miles).

One of the most memorable moments of the expedition was the near-catastrophe close to the Sudanese border.

The two vehicles bringing up the rear of the caravan had trouble keeping up. The lead vehicles stopped and launched a flare to signal their position. As the flare descended, it landed on a patch of dry grass, immediately igniting it. Despite their best efforts, nobody was able to put out the flames, which quickly grew out of control. As the fire spread, the drivers were forced to move on, lest they become trapped by the flames. Startled by the fire, a herd of animals now came stampeding toward the vehicles.

Luckily, all expedition members and vehicles survived the ordeal unscathed.

Before departing, André Citroën, founder of Citroën, estimated that his cars could complete the journey in under three weeks. His estimate was proven right: the journey was successfully completed after twenty days, when the mail the vehicles had been carrying was handed over to Colonel Mangeot, the French military commander of the Timbuktu region on January 7, 1923, thus completing the expedition and proving the Sahara Desert was conquerable by motor vehicle at last.

Legacy

Haardt and Audouin-Dubreuil continued their pursuits for the French military in cooperation with the Citroën Kégresse vehicles.

After the Sahara crossing expedition, they led the so-called “Black Cruise” in 1924-25, during which a convoy of eight half-tracks crossed the African continent en route to Madagascar, covering a total distance of 28,000 kilometers (17,500 miles).

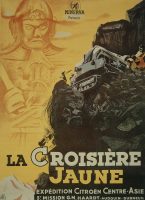

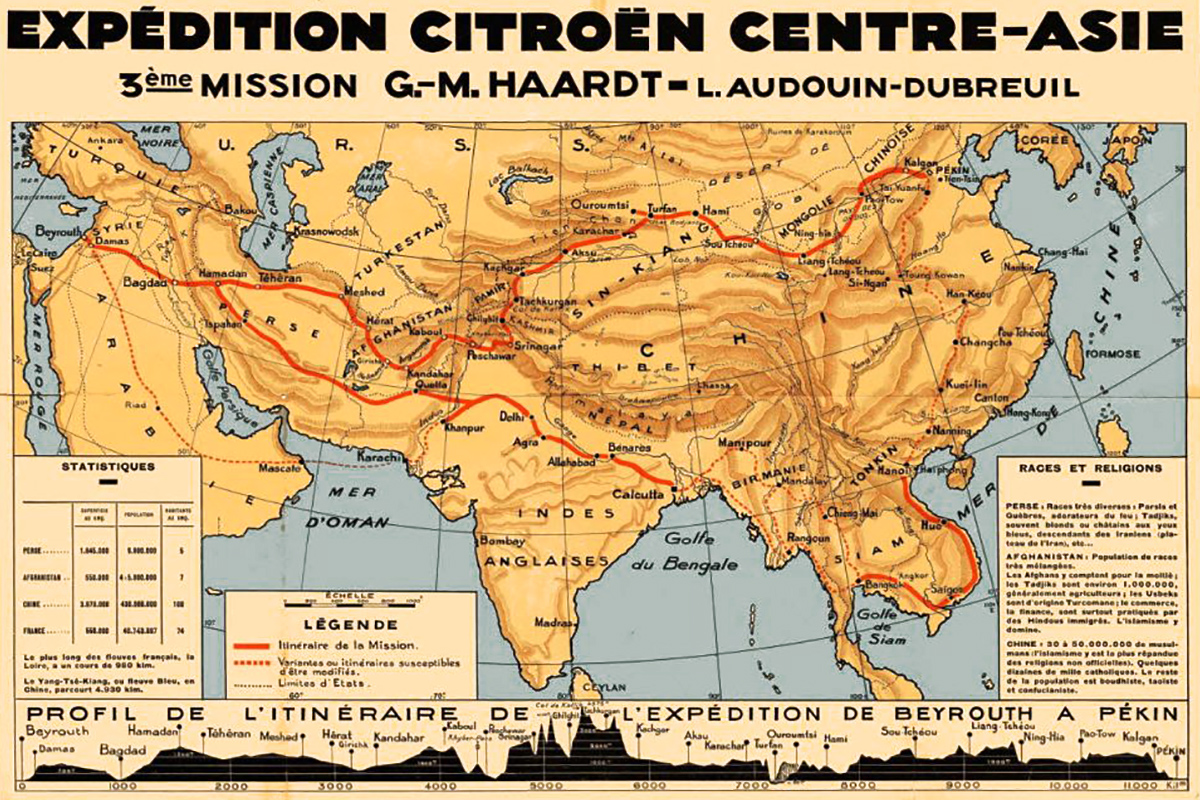

But the explorations did not end there. After conquering Africa twice, the sights were set to the East to opening up the fabled Silk Road to motorized vehicles. From 1931 to 1932, Haardt headed the expedition to China, a distance of some 30,000 kilometers (18,750 miles) from Beirut to Beijing, where they arrived on February 12, 1932.

Unfortunately, Haardt had fallen ill during this journey. Unable to return to France, he died in Hong Kong on March 15, 1932.

As for the Citroën Kégresse vehicles, they proved their worth during the expeditions. As André Citroën had predicted, the publicity from the successful expeditions was enormous. His half-tracks would eventually be produced by the thousands and saw service in the French and Polish armies in a wide variety of functions.

During the 1930s, a large number of military forces evaluated the concept of “endless” rubber tracks, most notably the US Army. Between 1940 and 1944, the US Army used 41,000 M2 and M3 half-tracks in over seventy different versions — all of which directly descended from the Citroën Kégresse vehicles of the 1920s.

This story first appeared in Gatehouse Gazette 2 (September 2008), p. 8-10, with the headline “The First Motorized Crossing of the Sahara”.