The foundations of history are held hostage by the whims of our predecessors — how Herodotus felt about the Spartans two thousand and five hundred years ago determines what we know about them today. A mathematical fact is an unflinching cinderblock of provable truth; an historical fact is no more than mutually consensual quicksand. How can we even begin to build objective structures in a field where everything we know can be overturned by a botanist discovering a scrap of North American tobacco in the stomach of a mummified Egyptian king?

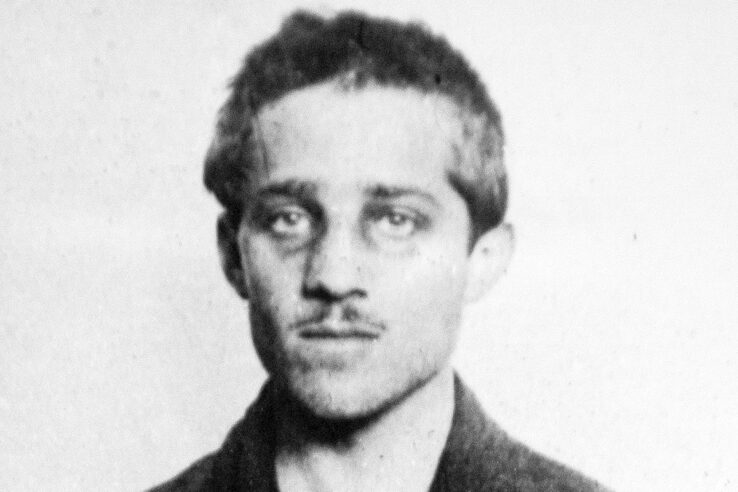

Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb and self-proclaimed Yugoslav Nationalist, was born on July 25, 1894. On June 28, 1914, he and five others set out to assassinate Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in an attempt to revitalize the Serbian struggle for independence. The events that preceded the attack played out much like a black comedy of errors; each assassin was given a weapon and a position on the archduke’s motorcade route, and each in turn failed at their task.

So much of what we know about the past hangs on nothing more than a scribbled word or phrase. So much of it is invented — sometimes out of necessity, sometimes merely out of preference — that we may wonder if any of it is true at all. For what purpose, then, do we study it? If there is no objective truth at the end of the rainbow, why bother seeking it out?

The first and second assassins failed to act; the third threw a bomb. It was deflected by Franz Ferdinand and detonated on the car behind him, wounding several people. In desperation, the assassin swallowed a cyanide pill and sprang into a nearby river, hoping to kill himself before he could be captured — only to discover the pill was old and ineffective and the river was six inches deep. He was pulled out of the water and severely beaten.

History is about telling stories of the past. Just like any story, it must respect the truth — but even the best stories are never really true. The past occurs only once. Any attempt to revisit it is an exercise in creative storytelling. And just like any story, it tells us more about the author than the event itself.

After learning of the failures of his cohorts, Gavrilo Princip reluctantly surrendered his high ambitions of regicide and set his goal slightly lower: finding a good restaurant. This brought him to a delicatessen known as Schiller’s, known throughout Sarajevo for its excellent ham sandwiches. He stepped inside and ordered that day’s special.

Steampunk is about revisiting the past with the knowledge of the present and reshaping it in a way that makes it pertinent and interesting to the now. It’s not historical revision, because it never claims to be “true” history in the first place; it’s history without history. More than an aesthetic, it allows us to discuss the now in the language of the then, expressing ideas that would otherwise be inexpressible.

Gavrilo finished his sandwich and stepped out of Schiller’s, only to find that the archduke’s motorcade was passing by at this very moment, traveling toward the hospital to visit those who had been injured in the first bombing attempt. Gathering his courage, Gavrilo ran forward and fired the opening shots of World War I. The economic disparities brought about by the Treaty of Versailles would lead inevitably to the Second World War. The oblivious architect of an era defined by conflict and genocide would be sentenced to twenty years imprisonment and die of tuberculosis in Theresienstadt, a place that would later serve as a Nazi concentration camp — and all because of a ham sandwich.

In the field of history, we cannot accuse a ham sandwich of defining the zeitgeist of an era; stodgy history professors shall descend upon us in a flurry of tut-tuts to rip our flimsy justifications to shreds. But in steampunk, it’s perfectly feasible — perhaps even likely. Because steampunk is fictitious by nature; it allows us to destroy history and rearrange its parts into a more fascinating and useful whole. Simply put, it lets us come closer to what history should be: interesting stories that tell us about who we are and from where we came.

So, World War I started over a ham sandwich. Who’s with me?

This story first appeared in Gatehouse Gazette 2 (September 2008), p. 4-5, with the headline “Of World Wars and Ham Sandwiches”.