Two rounds of Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) between the Soviet Union and the United States had managed to reduce tensions in the Cold War. But the talks did not cover tactical nuclear weapons delivered by midrange ballistic missiles, a loophole the Soviets exploited to deploy SS-20 mobile launch platforms in Central Europe.

When, in December 1979, the Soviet Union also invaded Afghanistan, the West felt it had to respond.

Cruise missiles in Europe

The American development of intermediate-range cruise missiles preceded the introduction of the SS-20 in Europe. But Leopoldo Nuti argues in “The Origins of the 1979 Dual Track Decision — A Survey,” published in The Crisis of Détente in Europe: From Helsinki to Gorbachev, 1975-1985 (2009), that the Soviet deployment did inform NATO’s Double-Track Decision, by which the alliance agreed to simultaneously deploy hundreds of mobile missile launchers of its own while continuing the SALT talks. The goal was to maintain a nuclear balance in Europe and avoid giving the Soviets the idea they might be able to win a nuclear war.

The technology came from America, but it were the European allies, particularly the British and the Germans, who were interested in deploying theater nuclear weapons in order to counterbalance the overwhelming conventional weapons superiority of the Warsaw Pact. The German government rejected out of hand suggestions it could dismantle American forward nuclear bases in exchange for Soviet concessions.

Division in the Netherlands

Opinion was more divided in the Netherlands. The country had been a stalwart Atlantic ally. The Dutch were the only European nation other than the Portuguese who were targeted in the 1973 oil embargo for their support for Israel and the United States. But now the Americans worried about growing Dutch opposition to cruise missiles.

The introduction of the neutron bomb in the late 1970s had split Dutch society and Dutch politics in half. President Jimmy Carter ultimately decided against deploying the weapon, but the same camps reformed around the Double-Track Decision a decade later. The center-right was in favor, left-wing parties were against. The ruling Christian Democrats were divided. Their left flank, including members of the Reformed Church, were opposed. The Christian Democratic right, predominantly Catholic, was in favor.

East Bloc security services tried to exploit the division in Western Europe. The East Germans had supported the Dutch Community Party when it opposed the neutron bomb. Now they sent money again to prop up resistance to the deployment of American missiles.

Prime Minister Ruud Lubbers, a right-wing Christian Democrat, stalled. Ronald Reagan, the new American president — who was blamed by the peace movement for reinvigorating the Cold War — had told Lubbers privately he no desire for an arms race. But so long as the Soviets refused to withdraw their SS-20s, the West could not back down.

Lubbers took until 1983 to agree to host 48 cruise missiles on Dutch soil. Even then, his government gave itself another two years to implement the decision.

Shuttle diplomacy

By October 26, 1985, time was running out. Lubbers was heaving breakfast with Rajiv Gandhi, the prime minister of India, in The Hague that morning. Hours later, he was due to address a massive peace rally in the Houtrusthallen.

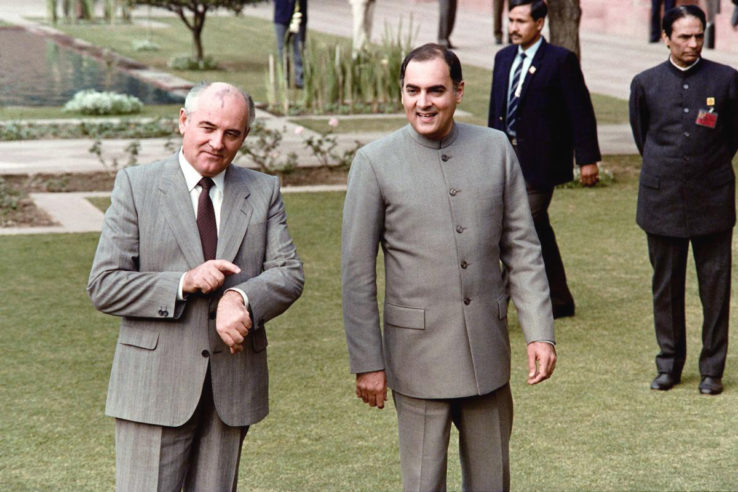

Gandhi was interrupted by a phone call. When he returned, the Indian apologized. The Russians had found out about his visit to The Hague and asked if he couldn’t stop by Moscow on his way back? Socialist India had close relations with the Soviet Union. A jet-legged Gandhi wasn’t looking forward to it, but Lubbers told me in 2012 he encouraged Gandhi to go and gauge the intentions of the new Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev.

When Gandhi phoned Lubbers a few days later, he had good news. Gorbachev wanted the Dutchman to know he was sincere about his arms-reduction talks with Reagan and said he expected a deal the following year. Gorbachev advised Lubbers to “get in the back of the line” and do what he did best — stall. So Lubbers did.

Gorbachev and Reagan signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in December 1987. The SS-20s were withdrawn. The Netherlands never saw American cruise missiles.

But on that October afternoon, Lubbers still had to face one of the largest peace rallies in his country’s history. He was handed 3.7 million signatures (representing a quarter of the Dutch population) from opponents to the deployment and had to defend his government’s decision, knowing Gandhi’s shuttle diplomacy might succeed and the Netherlands would never have to accept the weapons.

1 Comment

Add YoursThe Pershing II may have had a role elsewhere. I thought we were done with IRBMs-and here comes Agni and the gang.