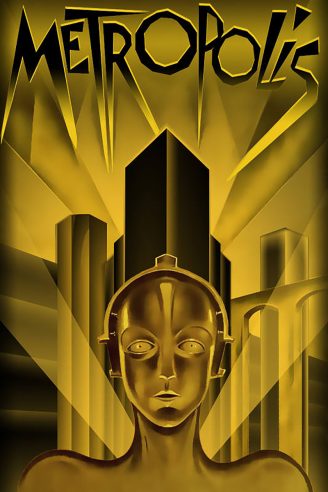

The 1927 film Metropolis is a milestone in the cinematographic genre of science-fiction and many reviews have been written about it, so I shall concentrate on two particular aspects and hope I am not plagiarizing someone else’s ideas.

Lang’s future, our present?

This question only concerns the timeframe. From a temporal perspective alone, Metropolis could be set in our time, being almost ninety years into the future at the time of its release. There are some elements in Metropolis which are amazingly accurate depictions of our present. Most of it, however, is not.

The society of Metropolis is extremely stratified, socially as well as spatially. A vast number of menial industrial workers toil and live in underground complexes while the elite dwells happily in towering metroplexes above ground.

The workers’ houses are actually deeper underground than the factories, somewhat reminiscent of the subterranean habitats of the Morlocks in H.G. Well’s The Time Machine (1895). Life for the workers is hard and often short. Fatal accidents at work seem to be fairly commonplace and are looked upon with indifference by the rulers.

Social interaction between the members of the elite and the workers is strongly discouraged and frowned upon. During most of the film, up until the very end, an antagonistic relationship between both castes dominates all interaction between them, broken initially only by Freder Fredersen, the son of the most powerful industrialist of the city, Johannes Fredersen, and later by his worker caste companions.

Also, Metropolis itself is, despite all its futuristic design, Art Deco and Modernist sky scrapers, a city in the industrial age, with its vast machine complexes underground and the aforementioned labor force. We see vast halls filled with dangerous machines, huge pipes and ant-like workers in uniforms, toiling along and, in some cases — like the worker who trades places with Freder — operating a device that looks like the face of a clock. So the vision of the future in Metropolis is positively rooted in the Industrial Age.

It is also rooted in the class struggle between workers and the bourgeoisie, which was rampant in the Weimar Republic of Lang’s time.

This vision seems to be a politically motivated one, although I dare not speculate about Fritz Lang’s political stance. Yet as so many futurist before him, he did envision the future based on his present. The skyscrapers are enormous, overgrown relatives of the Empire State Building; the machines look futuristic but can be recognized as industrial contraptions nonetheless. The workshop of the mad inventor Rotwang is reminiscent of a strange amalgam between Frankenstein’s laboratory and a metal worker’s shop. And, just like Wells and Verne before him, Lang imagines the social situation of his time to extend far into the future.

In retrospect, all these factors make Metropolis so fascinating and haunting at the same time. We live in Lang’s future and it turned out to be vastly different. There are no longer masses of exploited workers in the Western world. Although we are right now in a middle of a catastrophic economic crisis, the vast majority of the people affected have to make do with less, but this is still far more than any of the workers in Metropolis would have at the best of times.

In fact, the type of menial worker depicted in Metropolis has largely disappeared in the West, but is still a very accurate depiction of the traveling, unskilled workers of, say, China.

However, since Metropolis clearly is a Western city, we can safely state that the proletariat of Europe and America had a better fate than the one envisioned in the film. Rather, they have been largely replaced by various service-providers, from hairdressers to computer technicians. This broad swath of today’s society is completely absent from Metropolis, probably because Lang could not imagine them to factor in the future.

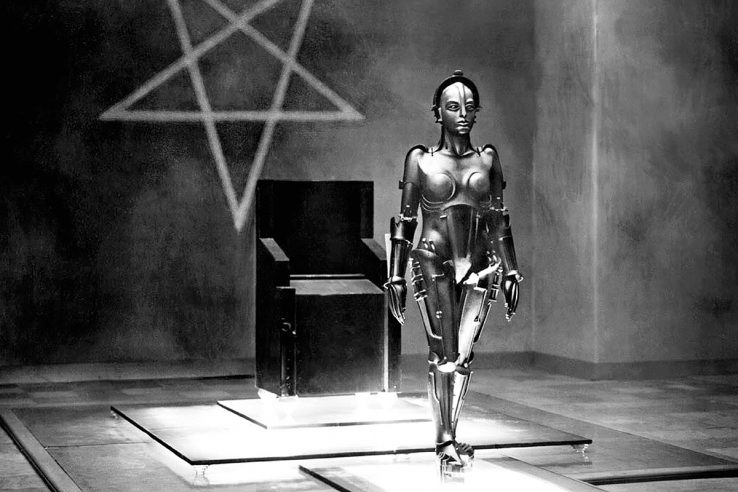

Also, there are no real human-like robots around and definitely nothing remotely similar or as advanced as Rotwang’s Maschinenmensch.

Interestingly, though, Rotwang explains to Fredersen Sen., his Maschinenmensch would be far better than human workers, no breaks, no mistakes, 24-hour shifts — which is more or less exactly the same reason why industrial automatons are employed today. In this regard, Lang’s vision of the future is frighteningly accurate, down to the actual words.

When we consider the bigger picture, however, we can all be happy that the future did once again turn out differently. Metropolis is therefore a place that can never be. Although it may have been likely in Lang’s time to exist at some point in the future, too much and too many things have changed. By the time we will have robots like the Maschinenmensch, there will very likely be no heavy machinery left to be operated by human workers, because these machines are already quite intelligent today.

Also, modern society is far less stratified than it was in Lang’s time and even less than it is envisioned in Metropolis. With the right skills and a good education, it is relatively easy to rise to a high-income position.

The dieselpunk perspective

From a dieselpunk perspective, Metropolis might be considered the cinematographic mother of the genre. I am not aware of any earlier film depicting so many elements of a dystopian dieselpunk society in such detail, but I am willing to be corrected.

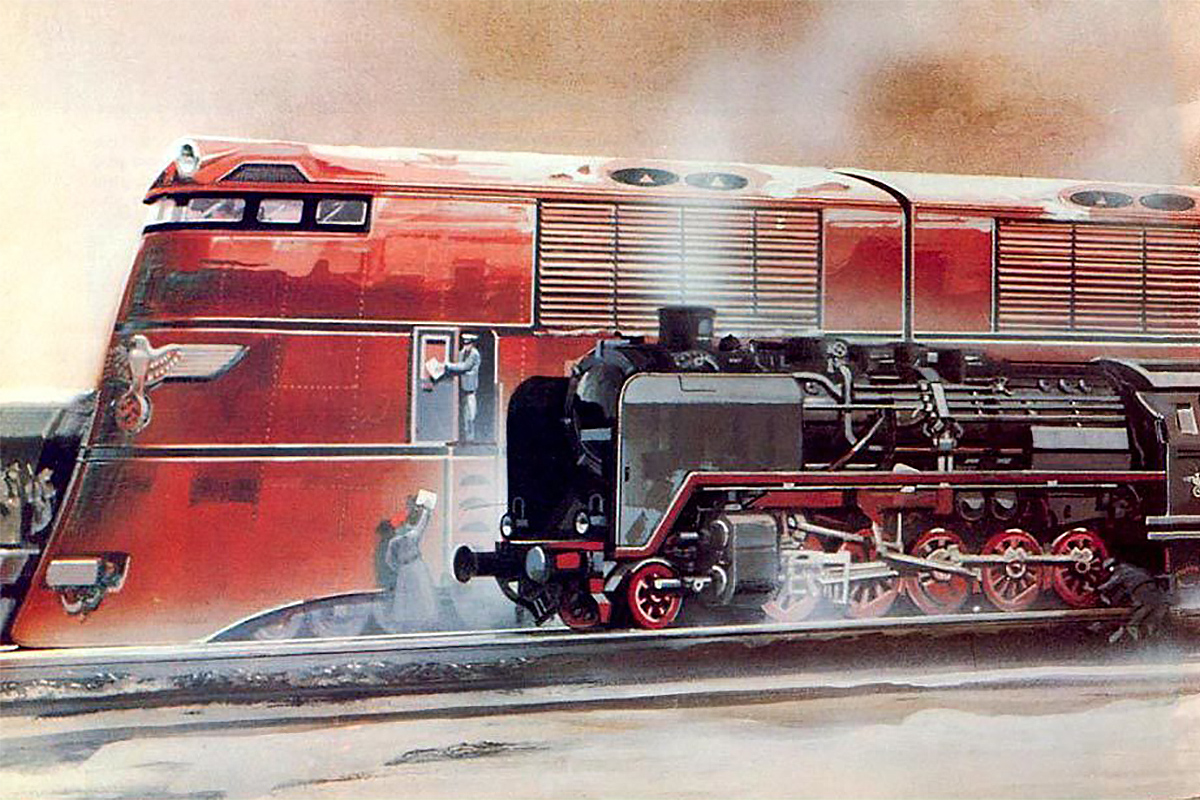

As I wrote, the city is still in the Industrial Age while vast skyscrapers dominate above ground. There are shuttle trains and highways connecting these hive-like buildings. Bi- and monoplanes and the occasional zeppelin fly in the chasms between these towers, which themselves come in a variety of futuristic shapes and are far grander than any building so far conceived in the real world.

The level of industrialization, in contrast, actually appears to be less advanced on some levels than it was even in Lang’s time. Although we have very advanced architecture, zeppelins and even robots, mass production, automation and machine tools seem to be non-existent. Instead, all these missing factors are compensated through the sheer number of downtrodden, exploited workers.

We can speculate that this is very much deliberately so. The living conditions of the workers are kept as primitive and toilsome as possible to keep them from having the extra time and energy to plan revolts.

With Rotwang the insane, haunted inventor comes another dark element of dieselpunk and a classic antagonist of the genre, just as his employer, the cold, plotting industrialist Johannes Fredersen.

In tow of the inventor enters the creature of weird science: the humanoid robot, powered by strange electrical force and transformed by the same into the likeness of a living young woman.

The character of the robot is another factor adding to the dark dieselpunk aesthetics: the automaton not only being near-human but near-woman adds a darkly erotic aspect to its existence, which later is only amplified by the tremendous power it shows luring and inciting both classes of Metropolis society.

The caste-defying love story adds melodrama to the film. Freder, son and heir to the most powerful industrialist, is in love with Maria, the angel of the workers. This relationship is not only instrumental in foiling the old Fredersen’s plot, but also in stopping the workers’ rebellion and witch-hunt to unite the ruling class with the proles in the final scene of the film.

Altogether, Metropolis features all the elements a good dieselpunk film should. Truly a masterpiece, far ahead of its time.

This story first appeared in Gatehouse Gazette 7 (July 2009), p. 4-5, with the headline “Future Lessons from the Past; Metropolis”.